Introduction

Some of my earliest memories of Australia are of our tiny, red-bricked flat and our boxy 1980s TV with its four channels where I watched children’s programs like Sesame Street and Play School. I loved these shows, and this is where my curious ear picked up some first words of English. Our family, and later my Cabramatta school friends and I, were translanguaging long before it became a pedagogical framework for teaching language. Most of us had come during the late 1970s and early 1980s by boat, or if we were lucky, by plane, sponsored by family members who had made it across earlier on the more treacherous ocean journeys. By necessity, we fled with just the clothes on our backs and in bodies tightened by fear and hunger. With the absence of anything of material worth, people held tightly to the culture and language of homelands they had left behind.

But my parents and many others also carried something else with them. Tucked quietly under the trauma was hope. They hoped that the sacrifice and their immense courage would allow their families to start a new life. At home, we were only allowed to speak Chinese dialects or Mandarin. I shed my Vietnamese because my father insisted on loyalty to the Chinese identity that had carried us through generational displacement. There was no space at home for English either. This question of identity and loyalty-by-language would become a reoccurring theme in all our lives and one which I recognise students in my EAL/D (English as an Additional Language/Dialect) classes and their families also wrestle with.

According to Baker (2011), translanguaging is the process of making meaning, gaining understanding and knowledge using two, or more, languages. The confluence of different dialects and languages in a single conversation was an everyday reality amongst my family and the immigrants within our community. My experience of the language of school, however, was a different reality. In the Australian classroom, the only acceptable language was standard Australian English, and we were defined by how well, or poorly, we grasped this. We implicitly felt that proficiency in English was required proof of our loyalty to the new country we now called home. But it left us, as young children, feeling conflicted about who were allowed to be, straddling as we did the distinct cultures of our home and school, each with their clear but conflicting rules about which language gained us acceptance.

This sense of otherness based around language is not unique to recent immigrants to Australia. Australia’s First Nations people have also been marginalised by the languages and dialects they do and do not speak, the disparities between the language of home and school, and the adherence to an assimilationist approach to language-use in the classroom. Like migrant communities, Aboriginal communities are historically multilingual and adept at using their full linguistic repertoire to communicate in socially appropriate and semantically sophisticated ways (Oliver et. al, 2021). Indeed, translanguaging is characteristic of multilingual communities around the world (Garcia & Li, 2014; Li, 2011).

To allow this as a pedagogy in our classrooms requires teachers to overcome the monolingual mindset that is a feature of our Australian identity (Clyne, 2006). It also requires teachers to value the role of home languages as a pedagogy for learning and growth that allows students to bring their whole selves to the classroom. It is likely my parents would have felt more at ease about allowing English at home if home languages were embraced at school. Instead, they steadfastly guarded against it, afraid that we would forget where we had come from, surrounded as we were by English in a country that was still getting used to its new wave of immigrants.

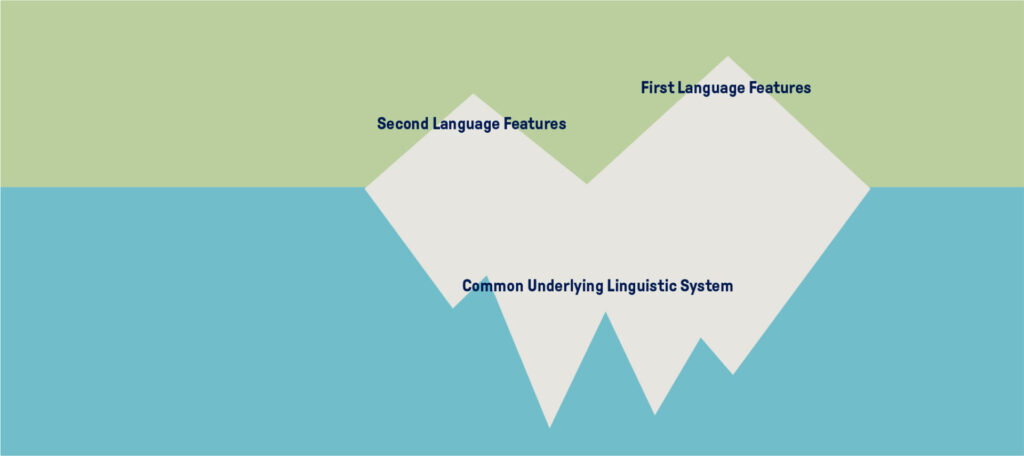

Figure 1: Adapted from Cummins’ Iceberg Model of Language Interdependence, 1981.

Translanguaging and what it means to be multilingual

To better understand translanguaging practices, imagine that languages are not discreet entities as such, but a unified linguistic system from which to draw (Otheguy et. al, 2015). Cummins (1981) iceberg model of language interdependence illustrates this concept graphically, with the tips of the iceberg appearing disparate while, beneath the surface, the peaks converge into one mass. The nuanced and dynamic ways that we communicate become apparent when multilingual speakers use language in ways which go beyond the constraints of any one language. Singaporean English, known locally as Singlish, is a case in point. Singlish infuses English with Malay and the various Chinese dialects spoken within the population. Below is an excerpt of a conversation in Singlish between two friends from a paper by Li (2018).

The above example of Singlish illustrates how being multilingual can also mean using multiple languages at once to communicate beyond the parametres of any one language while harnessing the cultural semiotic nuances of each. Translanguaging practices challenge us to rethink the monolingual view of what multilingualism looks like, namely that bilinguals have two distinct systems of languages which are used separately (Warren, 2018). Indeed, away from this monoglossic view of language, there is room to learn a new language and become multilingual, rather than to remain monolingual as the acquired language displaces an existing one (Li, 2018).

The young EAL/D students that I work with translanguage naturally in lessons, moving across English and Mandarin, using gestures and sounds to punctuate what they mean. These practices, and multilingualism in general, can be actively supported in the classroom through the teacher’s pedagogical choices (Beiler, 2021; Celic & Seltzer, 2013). My own teaching experience suggests that the ‘silent period’ of language learning, which is widely covered in research (Gibbons, 1985; Jang, 2008; Saville-Troike, 1988), can be mitigated using translanguaging practices in the classroom.

Translanguaging as a pedagogical practice

New York City is one of the most linguistically diverse places in the world, with over 800 languages spoken within its five boroughs (World Atlas, 2022). It comes as little surprise that a project like City University of New York – New York State Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals (CUNY-NYSIEB), spearheaded by the Research Institute for Study of Language in Urban Society, came about in the city to popularise translanguaging pedagogy and turn a critical light on existing ideologies around language, power and identity. To highlight the shift in pedagogical approach, the term “English language learner” is replaced with “emergent bilingual” or “multilingual learner” to recognise students as having existing linguistic capital (Celic & Seltzer, 2013). It gives tacit permission for students and teachers to value languages other than English in the classroom for teaching and learning purposes. How then, might translanguaging look in the classroom? And how does a teacher, without the benefit of proficiency in a student’s home language, manage teaching purposefully? Below are a few suggested ways for leveraging translanguaging as a pedagogical tool in the multilingual classroom. Further details and strategies can by explored on the CUNY-SYIEB website https://www.cuny-nysieb.org/.

Creating a multilingual ecology

To create a multilingual ecology is to design a learning environment where multilingual learners and their families, feel represented in the resources, content, topics, celebrations and discussions that take place (Celic & Seltzer, 2013). These include the use of culturally relevant texts that reflect a student’s background or lived experience. When I have mentioned the benefits of using home language storybooks at home to parents of my EAL/D students, the sigh of relief is almost palpable. Aside from the benefits to students in the classroom, books in a language they understand gives parents the power to support and connect with their child on their language learning journey.

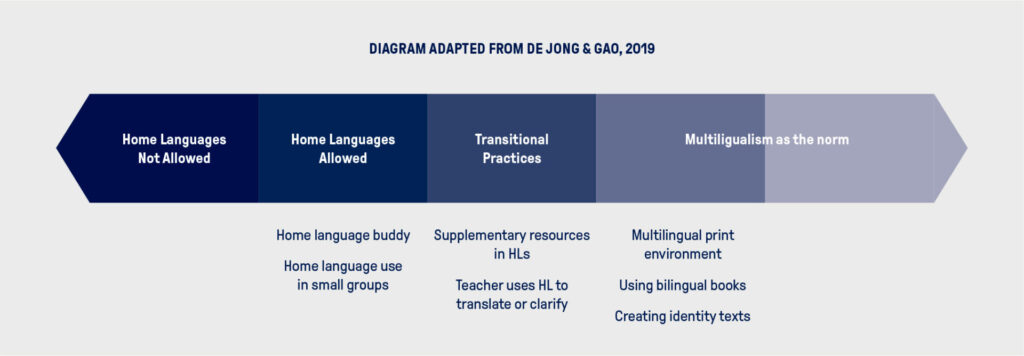

Another example is to produce identity texts where students create a bilingual text in English and their home language to share their cultural and linguistic identities and experiences (Cummins, 2005). Multilingual auditory texts, songs and chants which are especially appealing for younger students who are not able to read, but still highly engaging for older students, are also valuable multilingual resources in an inclusive classroom. Figure 2 is a diagram of a continuum showing how the shift towards a diverse language ecology in a classroom might occur.

Figure 2: Continuum showing a shift towards diverse language ecologies in a classroom, adapted from de Jong & Gao, 2019.

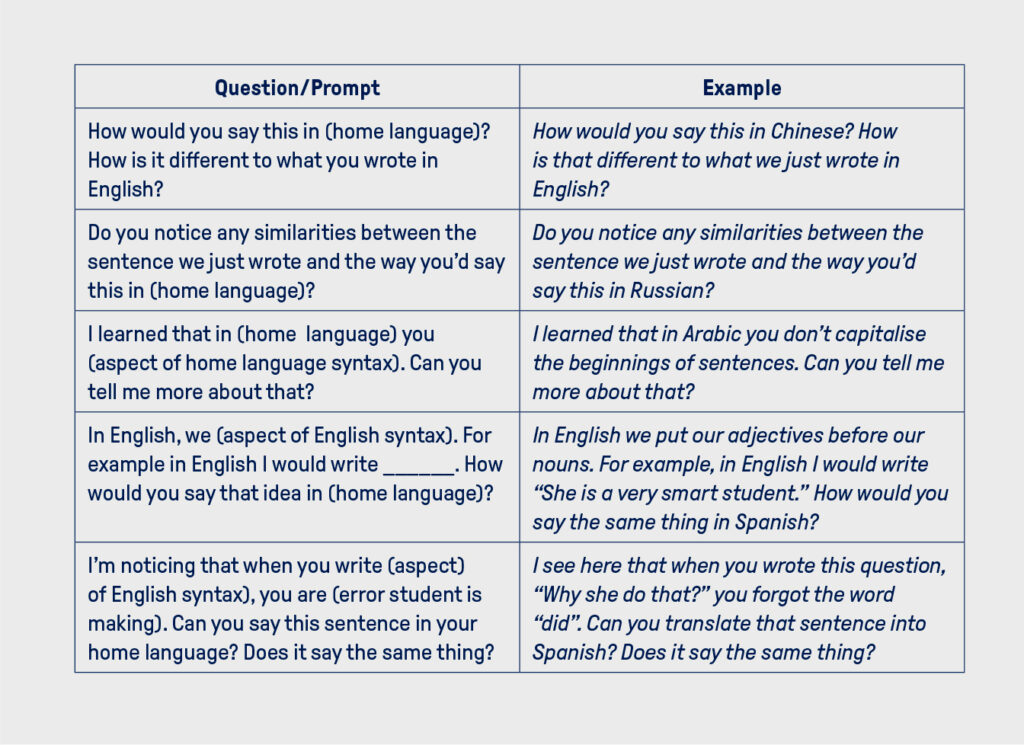

Prompts for comparative language analysis

In my teaching practice with my EAL/D students, I have found comparative language analysis to be useful when discussing grammatical differences between a student’s home language and English. This appears to help students reflect on some of the reoccurring mistakes they might be making and hone in on the features of English of which they need to be more conscious. The table of comparative language analysis prompts below, taken from the CUNY-NYSIEB guidebook on translanguaging practices, provides suggestions on the types of questions you might ask to generate awareness in yourself as well as your students.

The Traffic Light System and home language use

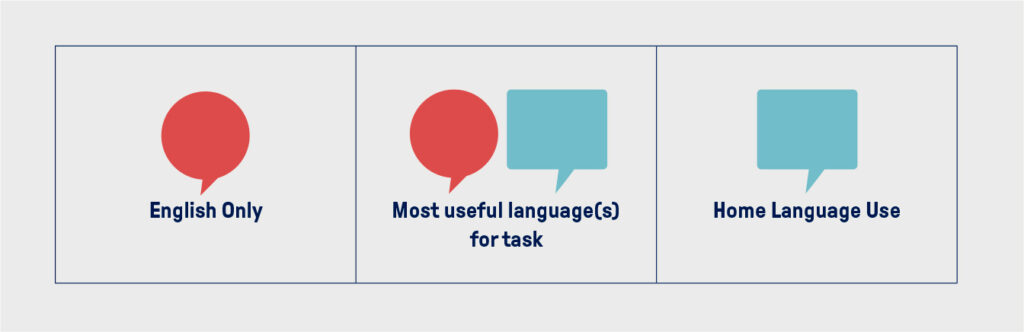

Translanguaging is very much a student-centred approach, where relationship and trust matters, as do intentionality and clear guidelines. Another possible strategy for bringing intentionality to a multilingual classroom, particularly when a teacher does not speak the students’ home language(s), is through a traffic light system for when home languages, English or both are required for a classroom task.

For example, red-coded activities might be ones which require students to speak only in English. An example of this might be a presentation on content that has been covered over several lessons. An amber-coded activity might be one which allows students to choose which language to work in. An example might be a small group discussion around a given topic. A green-coded activity might be one which allows students to work exclusively in their home language. An example of this activity might be researching in-depth on a given topic.

The potential flip-side to using this traffic light analogy to moderate language use in the classroom is the implicit prohibition signaled by the colour red. Another imagery such as Figure 4 which illustrates the range of languages that is constructive for a given task, might be useful without the negative undertones.

Allowing students to move in and out of languages also allows them to bring viewpoints that are unique to the linguistic features and cultural lens of their languaging repertoire. Not only is this a form of social justice that makes space for the languages and identities students bring to the classroom, but also cognitive justice in recognising an alternate interpretation, adding to the richness of their individual and collective learning experience.

Figure 3: CUNY-NYSIEB Translanguaging Guide, 2013.

Figure 4: Visual codes for use in the multilingual classroom

Language profiles

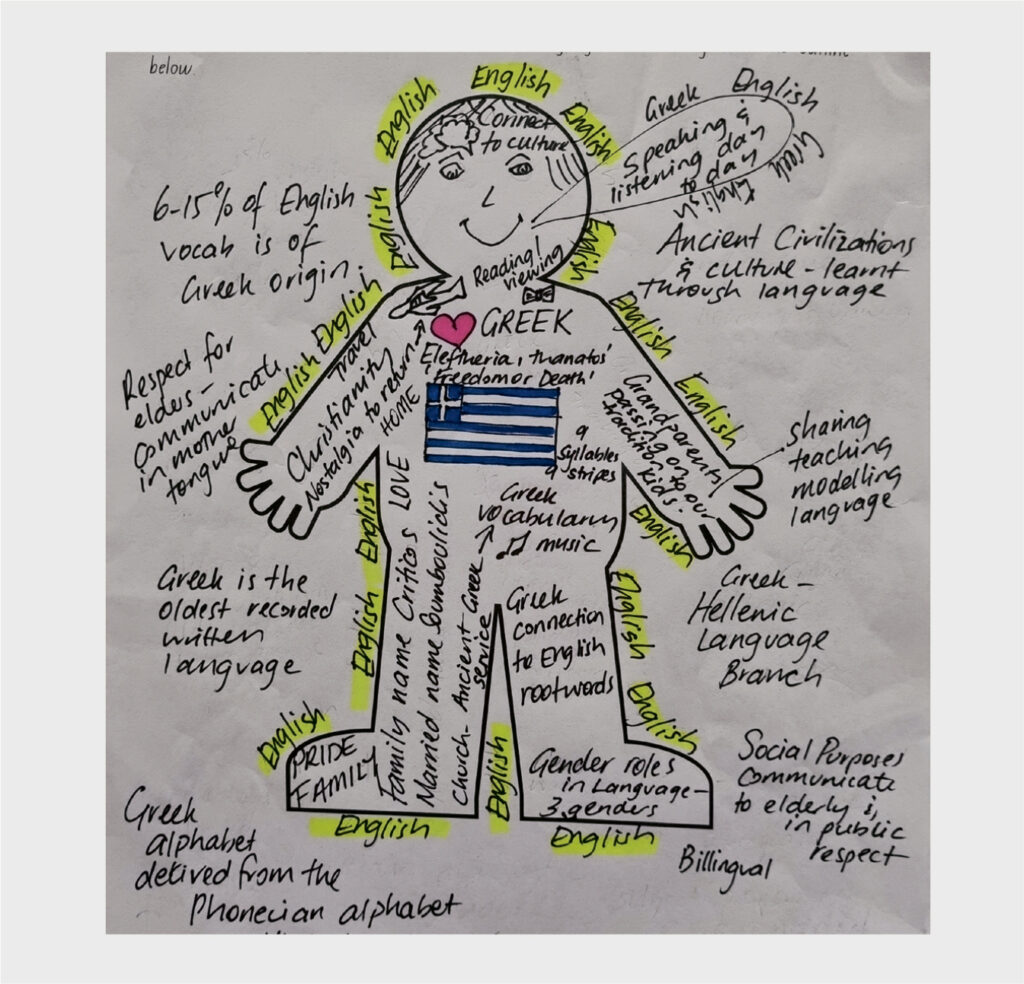

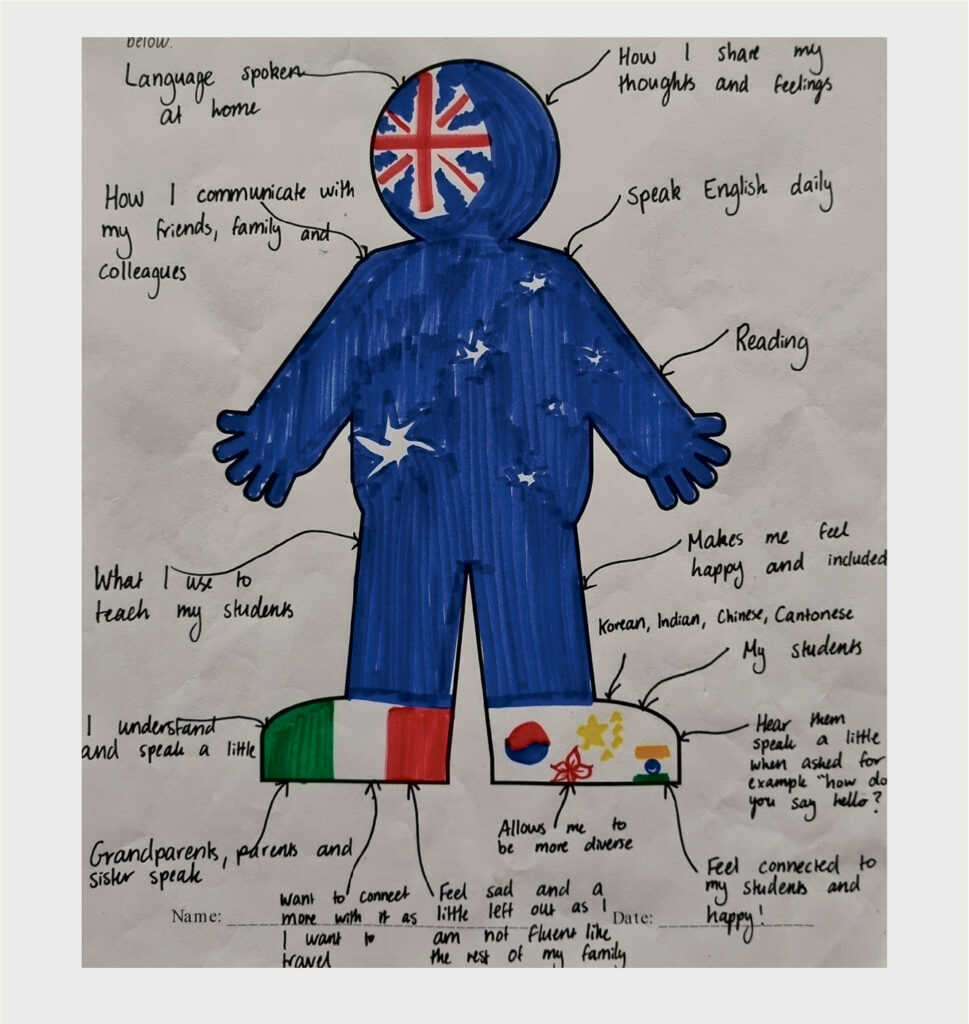

As Oliver et. al (2021) pointed out, enacting translanguaging practices in the classroom require a number of enabling factors, including teacher awareness and recognition of a student’s existing language knowledge. Chik et. al (2018) authored a research paper called “Languages of Sydney: The People and The Passion” which used a simple human outline to create a ‘language portrait silhouette’ of student teachers. The idea behind the project was to celebrate the richness of our individual, as well as combined linguistic diversity, and to showcase the intimate connection between language and identity. In total, sixty-six language portrait silhouettes were curated, showing the tapestry of languaging practices in a cross section of Sydney. In a school setting, such language portraits would be instrumental in determining what language resources and cultural identities students are bringing to the classroom. From this, teachers can then design translanguaging learning activities to suit the needs of the class.

The first two language silhouettes below are examples completed by Pymble Ladies’ College colleagues to represent the connection they have with languages in their repertoire. Victoria, who completed the first silhouette, noted how much she enjoyed the process of delving into how language connected her to her Greek heritage and how this shaped her sense of self. Liv, who completed the second silhouette, noted that while she was of Italian heritage, she only spoke English. Yet her profile shows a respect for her heritage and an appreciation for the languages of the students in her class.

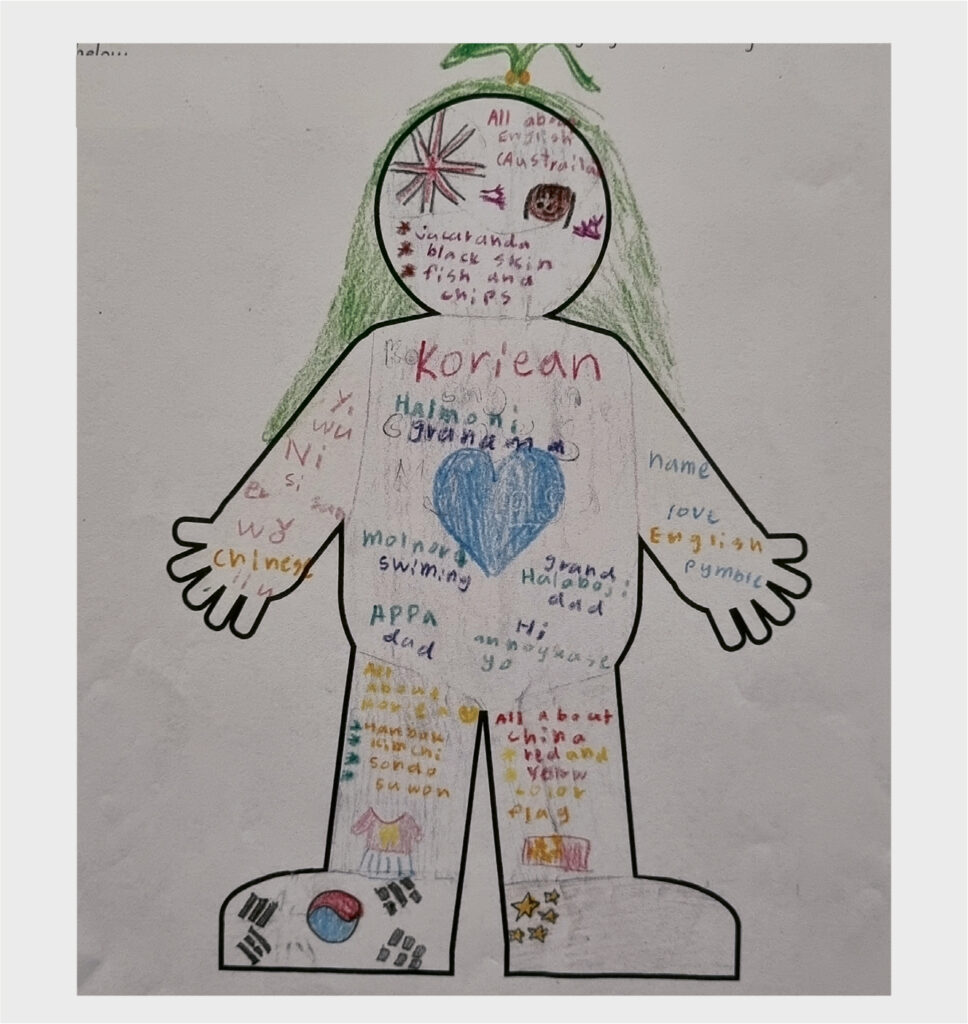

The third silhouette is by a Year 1 EAL/D student with Korean as her home language. Here my student has marked the places on her body where each language resides. English, a new language, is in her head, with green hair sprouting to show how it is helping her grow. She also includes things she associates with Australian culture. Korean, her home language, resides in her torso, surrounding her heart. Here, she has written the Korean and English words for different members of her family and the greeting “Hi”. Each of her limbs are adorned with the languages she uses or is learning, namely English, Chinese and Korean. For someone so young, she has shown an intimate understanding of the power of languaging in her life.

Figure 5: Victoria’s language silhouette

Figure 6: Liv’s language silhouette

Figure 7: Year 1 EAL/D student’s language silhouette

Conclusion

In a multicultural society such as Australia, there is a cognitive dissonance to teaching and learning English through a monoglossic, assimilationist approach that overlooks a student’s established linguistic repertoire. This narrowed view defines students in terms of what they are lacking and requires them to leave their home languages, and a fundamental part of who they are, at the classroom door. Understandably, teachers may otherwise feel remiss for not maximising their students’ exposure to and practice with English, the target language. As EAL/D teachers, we are often asked the question, “is it alright for students to speak [insert home language] in class?” or “shouldn’t they only be speaking English at school?”.

Yet, students should be able to bring their whole selves to the classroom, and this means recognising the value of the languages they already have, not just the void of the English they do not have. When I was learning English in the 1980s, not long after the White Australia policy was finally abolished, this ‘speak English only’ stance was normative and unquestioned. Our current, residual imperative to ‘use English only’ is also a legacy of this part of our assimilationist, colonial history.

It is time to move on. To this end, translanguaging is a pedagogical asset. It challenges monolingual assumptions underlying language education policy and refers to pedagogical practices that views multilingualism as a resource rather than a deficit. In this way, translanguaging moves beyond traditional notions of multilingualism and additional language teaching and learning. To fully embrace the richness of our diverse human capital, translanguaging offers a shift from monoglossic views of how we see language towards an openness to the linguistic and cultural resources our students bring to the Australian classroom.