His / her-story: The value of historical literature in the History curriculum

May 15, 2023 | Secondary School

Abstract

History as a school subject has experienced some wins but also some losses in recent years. While it was identified as one of the four key learning areas in the Australian Curriculum, there has been a decline in school and university students opting to study history as an elective. This article explores the value of historical literature to historical learning and literacy within schools. In particular, the role of the teacher librarian in promoting the reading of historical literature and its use as a resource within the classroom is a key focus. Could the use of historical fiction as a pedagogical tool prove to be an effective strategy in luring students back to the study of history?

Introduction

The term ‘historical fiction’ can be defined as realistic fiction that is set in a historical setting (Crawford and Zygouris-Coe, 2008, p.198). While the value of historical fiction in the history classroom has long been debated (Howell, 2014, p.4), the focus of this article is on the benefits historical literature can bring to the 21st-century curriculum with the teacher librarian as a key facilitator. These benefits include student engagement, increased historical literacy, enhanced empathetic understanding and a greater connectedness to citizenship. These issues are explored regarding secondary History – Stages 4, 5 and 6.

Key Issues – History in the present

To judge the value of historical fiction in the History curriculum, it is necessary to first explore some of the recent developments and trends in history education. Firstly, the national roll-out of the Australian Curriculum for Kindergarten to Year 12, implemented from 2013, has brought with it a set of fresh challenges for History educators. History was identified as one of the core key learning areas, alongside English, Mathematics and Science. While this was welcomed by many in the history community (Howell, 2014, p.5), it also raised some concern as student numbers in non-compulsory History stages has been declining. For example, a study of enrolment patterns over the last five years in senior Ancient History in New South Wales shows that there has been a steady decline in student numbers. The subject has lost approximately 45 per cent of its candidature between 2010 and 2022 (NSW Education Standards Authority, 2022). This pattern has also been replicated at the tertiary level with a decrease in the number of History pre-service teachers (Howell, 2014, p.5). Alarmingly, Rodwell (2013, p.10-11) uses words such as “bored” and “ill-trained” to describe student teachers training to teach history in school. This downturn in popularity, coupled with the renewed focus on STEM skills and subjects, has history academics and educators questioning what can be done to reverse this trend.

Another issue that arises from recent developments in education is the recognition of multiple literacies. The definition of literacy has evolved from the ability to read and write to a far more complex concept. This is a result of changes in educational theory and rapid technological developments. Donnelly explains that the definition of literacy today includes “visual, media, digital and internet literacy and the ability to move with fluidity between communication platforms” (2017, p.43-44). She stresses that it is this ability that allows individuals to be active citizens in their community. Similarly, the concept of historical literacy has expanded from an understanding of dates, people and events to a more multi-layered model. Students are expected to consider a multitude of historical sources (textual, visual, digital) in a critical manner to ascertain the ideological meaning behind these sources (Donnelly, 2017, p.44). This is reinforced in the document developed by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) on the aims of the national History curriculum. It summarises that “students develop a critical perspective on … versions of the past” (2009, p.5). In the already crowded curriculum, educators are tasked with not only with teaching students to read and write but also to be critical thinkers.

While values education is not a new concept within the teaching of History, the Australian Curriculum certainly places renewed focus upon the values History can instil. The New South Wales Education Standard Authority’s K-10 History Syllabus clearly states its hope that the study of History will bring about the opportunity for students to “contribute to a democratic and socially just society through informed citizenship” (2012, p.12). In addition to informed citizenship, the syllabus also highlights the desire to develop “empathetic understanding” (p.19-21) in students. Teaching an abstract emotion such as empathy is not easily done. Lip service is often paid to empathy within history education, but it is difficult to gauge just how empathetic students are feeling towards past peoples or events. Martin and Brooke (2002) discuss the challenges of teaching empathy and highlight the “criticism levelled at empathy” (p.30) due to superficial empathy writing exercises.

Value to the collection – So what does historical literature have to do with any of this?

The integration of historical literature into the History curriculum is a promising and exciting opportunity to help tackle the challenges mentioned above (alongside the excellent work of many Australian History teachers to foster a love of history and develop historical literacy amongst students). The school library and teacher librarian can play a pivotal role here. A varied and up-to-date historical fiction section can aid in building student engagement in history, enhance historical literacy and elicit empathy from student readers.

“At its essence, history is about the story of people from the past. It is only natural that story is used to tap into the human experience and build connections between people of the past and the present day.”

An increasingly loud chorus of academics champion the use of historical fiction to place the sometimes-dry content of history within a more human narrative. As Rycick and Rosler (2009, p.163) so eloquently explain “reading historical fiction provides students with a vicarious experience for places and people they could otherwise never know”. It broadens their understanding by placing a possibly unfamiliar setting and people within the familiar patterns of story. Stories are often more enjoyable than a list of facts (Crawford and Zygouris-Coe, 2008, p.197-198). This is the starting point for the significant value of historical fiction within the curriculum. An illustrative example of this is Barb Alexander’s (2015) narrative on the Tudor dynasty, The Tudor Tutor: Your Cheeky Guide to the Dynasty. While a work of non-fiction, Alexander tells the story of the Tudor family with hilarity and modern-day, colloquial language, appealing to socially connected teen readers. By embedding the details, dates and facts of the ruling Tudors within an amusing story, it provides a much more memorable learning experience than a textbook, especially for differentiating between the many Thomases and Katherines of the period! The many watercolour-esque illustrations throughout, further maintain student interest and literally paint a picture of these intriguing historical figures.

Haven’s studies on the efficacy of story (2007, p.90) reinforce this. He concludes that individuals more readily comprehend and retain information when it is presented in story form. This suggests a promising foundation for the use of historical fiction in the history curriculum in helping students to understand detail in the first place and recall it at a later date. Story can play an important role in triggering prior knowledge. Therefore, the use of historical fiction to introduce a topic can be a positive way to help students feel engaged and connected with the content and stimulate excitement. For example, Christina Bailit’s (2003) picture book Escape From Pompeii makes for a memorable start to the core HSC Ancient History topic on Pompeii and Herculaneum. It stirs students’ prior knowledge and provides historically accurate narrative of the eruption of Vesuvius, while following the experience of two fictional Pompeiian locals affected by the disaster. Although this is a book originally written for a younger audience, older students still enjoy the nostalgia of being read to, the graphic illustrations of the destruction and the familiarity of the story pattern.

Story continues to have an important place throughout an historical unit. It helps to consolidate historical details and assist students to make meaning of these details, thereby stimulating higher-order historical understanding (Rodwell, 2019, p.194-195). For a content heavy subject like History, this is vitally important. The graphic nonfiction novel Cleopatra: The Life of an Egyptian Queen (Jeffrey and Ganeri, 2005) is a helpful teaching tool for students studying Cleopatra as a personality in upper Stage 5 History. The combination of the text telling the story of Cleopatra with the comic style illustrations by Ross Watson, help unpack the somewhat confusing tale of the Egyptian queen. The graphically presented dialogue and thought processes of the characters encourage students to better understand the actions and motivations of these foreign people who lived 2,000 years ago. The theory behind this is nicely summed up by Haven, “the use of story structure facilitates and enhances the creation of meaning” (p.108). Leaping ahead in time, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s app Gallipoli, The First Day (2015) is an outstanding resource that evocatively brings to life the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli. Using simulated animation and minimal text, the app walks the viewer through the stages of the failed landing. Perfect for Stage 5 World War I History, students are caught up in actions of the ANZACS and Turks. This historical recreation is far more powerful in making historical meaning than reading a textbook. It also elicits great empathy for the ANZACS and Turks as their perspective is brilliantly portrayed in the animations.

“Historical fiction plays an important role in creating empathetic understanding in students. By following the actions and feelings of fictional and non-fictional characters in an historical setting, students can forge a more emotional, and therefore empathetic, connection with the past.”

While discussing fiction in general, Gaiman (2013) passionately links fiction and empathy, “you get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well”. This beautifully encapsulates the intent of the previously mentioned NESA Syllabus (2012) regarding the empathetic understanding of students with the past. While a fictional account, the novel The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (Boyne, 2006) provides the opportunity for great empathetic understanding with victims of the Holocaust set against the backdrop of the horrors of the Final Solution. Similarly, the interactive website designed by the Anne Frank House Museum allows individuals to conduct a virtual walk through of the annex in which the Franks lived in hiding from the Nazis. Extracts from Anne’s Diary accompany the journey through the house. The combination of the visuals from the house, with the first-hand accounts provided by Anne, vividly bring to life the experience of their years in hiding and elicit a profound empathetic understanding.

Like empathy, the spirit of citizenship can be more successfully promoted through stories, rather than simply telling students they need to be informed citizens of Australia and the world. The Australian History section of the Stage 5 Syllabus (NESA, p.79) provides great opportunity here. Historical fiction based on the experiences of Australian soldiers (and their foes) during World War I reinforces historical understanding (as previously discussed) and helps students to explore the actions of Australians who have come before that have contributed towards nation building. Picture books such as The Soldier’s Gift (Palmer and Tanner, 2014) and My Gallipoli (Starke, 2015) can be used in class to generate discussion on the qualities of citizenship demonstrated in the texts. This could be part of a broader exploration of the ANZAC Legend.

The role of the teacher librarian

It is quite easy for a History teacher to use a few pieces of historical literature in their methodology. However, to really tap into the significant benefits outlined above, a collaborative working relationship between teacher librarian and history teacher is vital. Firstly, it is important for the teacher librarian and classroom teachers to discuss topics under study so that the school library can curate a quality historical literature section that reflects the topics being taught. The result of this is that teachers will have a good selection of literary resources they can use within their methodology and students have a broad collection of titles they can read for pleasure and to deepen their historical literacy. Ideally, the literary works will be a mix of text types to suit different tastes and learning styles.

The relationship between teacher librarian and classroom teacher can, and should, run deeper in utilising historical literature in the curriculum. The teacher librarian is a great resource for the history teacher to work with to develop units and activities on student historical literacy using historical literature. The foundation of literacy (Haven, p.104), in this case historical literacy, is comprehension of the historical detail. The next step is to make personal meaning and connections. A more sophisticated step, especially focused on in secondary school history, is to think critically about these details. In other words, to consider if the details and perspective in the source can be trusted. This is an area in which the teacher librarian can be most helpful.

“With their strength in digital literacy, combined with their knowledge of the historical literature genre, the teacher librarian can assist teachers and students to question the validity of historical literature.”

Their role could range from supporting the classroom practitioner with sourcing appropriate literature and resources to team teaching critical literacy skills alongside the history teacher. An activity that could work well in a team-teaching scenario is where students apply their knowledge gained from the classroom and more traditional historical sources to a piece of historical literature on the same topic (Fink, 2018). The text is critically analysed for its value as a source.

Taking this critical literacy a step further, student construction of historical fiction provides an opportunity for students to demonstrate their knowledge of an historical period and historical veracity. As the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy suggests, to create is the pinnacle of critical thinking (University of British Columbia, 2011). The library as the hub for learning within a school is in a prime position to facilitate an historical fiction writing project or competition. Cross-curricular collaboration with the History and English departments would be ideal. The Each Project in the UK (Martin and Boothe, 2002 p.30) promotes the writing of historical fiction in schools to further student historical understanding and empathy. Their approach “stresses the importance of rigorous historical research and careful attention to style and genre” (Martin and Boothe, 2002 p.30) therefore highlighting the overlap between history and English that a teacher librarian could help facilitate.

“The physical space of the school library can be used to promote historical literature. Teacher librarians can create engaging displays promoting historical literature in general or focus on a particular historical period. This could be linked to a topic being covered in history classes at the time to encourage students to read some related literature and immerse themselves in a story set in that time.”

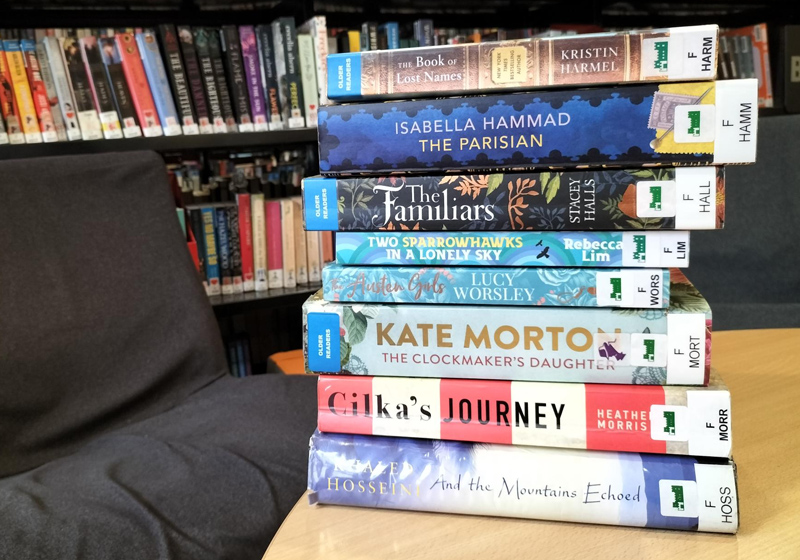

The library fiction shelves could be more permanently reorganised to group works according to genre, including an historical fiction section. There are a range of benefits to this, as highlighted by The National Library of New Zealand (n.d), such as a less daunting fiction collection, increased useability as students can more easily find a book in a genre they enjoy, and the teacher librarian can easily showcase books in a particular genre. Interestingly, libraries that have moved to a genre arrangement have seen an increase in borrowing (National Library of New Zealand).

The teacher librarian can instigate other initiatives to promote the profile and value of historical fiction such as reading guides and reader polls. Teacher librarians can curate reading guides of new and/or favourite works of historical fiction. These can be printed and placed in a highly visible part of the library and advertised on the library homepage. The guides can be organised according to topic, again linking to the topics covered in Stages 4, 5 and 6 of the History courses. Online polls can also be implemented to encourage students to vote for their favourite works on historical fiction, with the results to be showcased in the library and on the library homepage. The aim of this is to generate some buzz around historical fiction, raise its profile and have some fun.

Conclusion

Historical literature has a place within the History curriculum. It is proven to increase student engagement with the subject, improve historical understanding and help develop historical literacy. Straddling the two worlds of literature and curriculum, the teacher librarian is in a key position to facilitate the increased use of historical literature within the curriculum.