Creating worlds of research in their school

July 24, 2022 | Junior School , Pymble Institute , Secondary School

Introduction

School-based research centres of different kinds are growing (Furze, 2022) and are well positioned to act as a hinge between school communities and university faculties and researchers. Launched in 2021, the Pymble Institute is one such centre. Its mission is to conduct research and professional learning which drives thinking forward to improve outcomes for women and girls. A strand of the Pymble Institute’s mission relates to activating critical awareness towards research amongst students and increasing students’ skills and opportunities in conducting and using research to change the world.

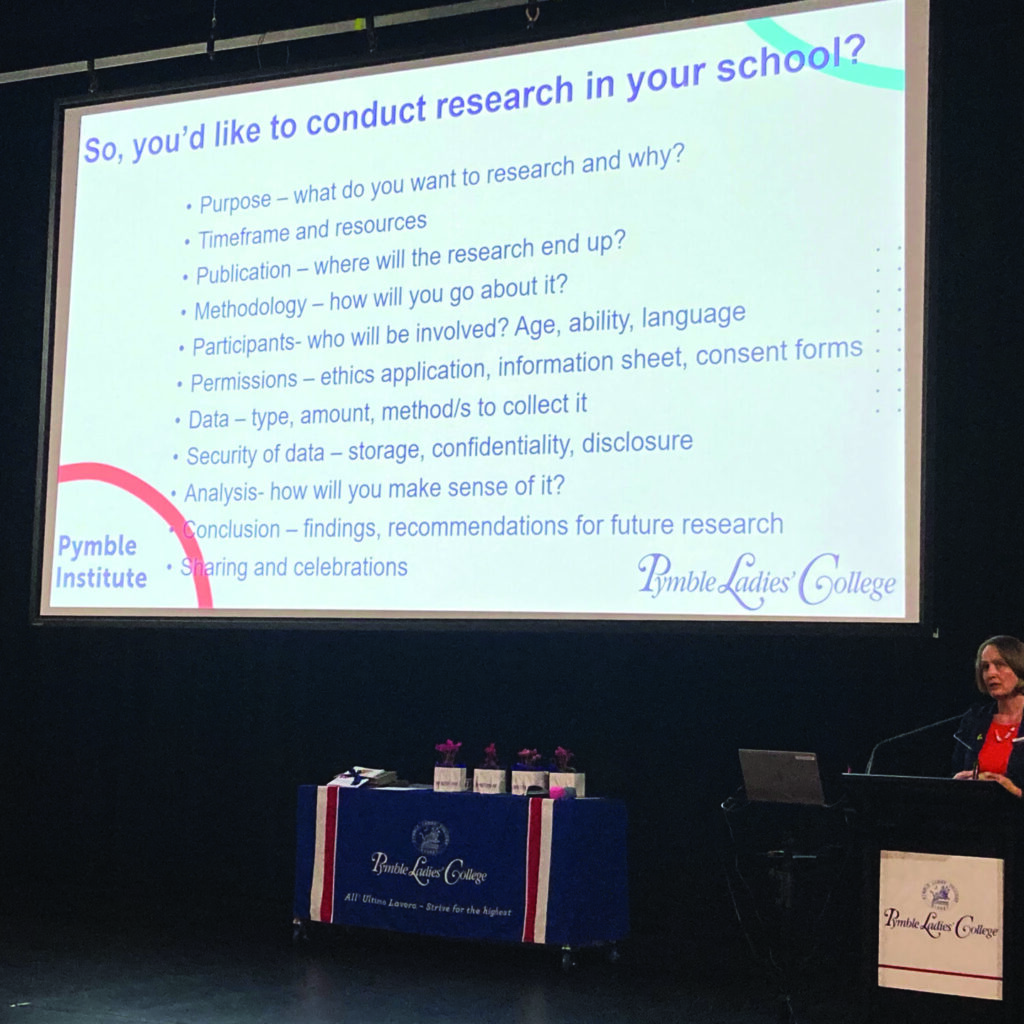

As director of the Pymble Institute, I am responsible for building the research culture in the College. I began by supporting teachers and students to undertake inquiry and research, then, to grow the culture further, began intentionally translating activities from the (tertiary) world of research to the (primary and secondary) school context. This student-focused aspect, with activities clustered around research design, ethical processes, data collection, analysis, findings, and written, verbal and visual communication of research, has been developing for a few years, and I am surprised by how well tertiary-based research activities have seeded in the school context.

Whilst pleasing, this success is raising new questions and there is merit in critically retracing the terrain traversed, hence the focus of this paper. This paper considers ways tertiary-based research activities provide a good fit and benefit for students at Pymble, but I also question whether existing structures could restrict school students’ perceptions of research.

Research in a school

Schools with research centres, currently usually the larger, independent schools, can develop their own centres according to strategy, mission and opportunity. Visits to a number of schools in the USA and Canada, with established research centres, revealed these centres can serve a specific pedagogical purpose (e.g. to conduct research into training teachers to teach in a certain way) or a specific culture and wellbeing purpose (e.g. to conduct research in and present research about topics that the school is championing) (Loch, 2020). They can also act as portals through which universities connect with the school to conduct research, and provide opportunities, support and networks for school staff undertaking action research or postgraduate studies. The relationship with students and ways students connect with the research centre is especially important in my context, but is not a key feature of all school-based research centres. The focus of most school-based research centres seems to be adults – teachers, other school staff, university academics and researchers from other organisations – and inquiry into teaching, learning, leading and pastoral care for children and young people. To this end, contributing to research into what a research-culture looks like in a school with students at the fore and core is a timely and important endeavour. As there are limited models for ‘creating a context where action and research are tightly connected …. [to] develop an approach to social change together’ (Keddie, 2021, p.11) through student perspectives, this is a valuable area to explore.

Four stories – Building a research culture with students in mind

I begin with a reflection on what a good fit conventional, research-oriented behaviours appear to be in my school. Pymble students, from Junior School to Year 12, working with me on committees, projects and events, seem inspired by structures more commonly used by university students and academics than school students. My reflections lead me to see how we are building research culture at Pymble by giving students opportunities to behave like researchers. They appear energised by invitations to get involved with research and in sync with my belief that they can go further and deeper into projects that matter to them by learning languages and protocols of research. I witness meaningful intellectual growth as students volunteer to write and re-write survey questions for areas they wish to investigate more fully. I see students work in teams to analyse survey data; participate in or help run focus groups to collect different data; create presentations or posters for peers which give feedback on research students participated in; organise to meet professional researchers to ask about their work before committing to a project with them, etc.

The following four stories illuminate aspects of students’ experiences and ways the research culture is being shaped at Pymble. The first is from the school ethics committee where an application from a PhD researcher is reviewed. This experience reveals the expertise students bring to research ethics. The second recounts a data collection activity with primary students and highlights creative and open-ended ways to do this. The third gives insights into the co-planning of a research conference with the student convenors of the event, and the final story shares the evolution of a student academic research club.

Ethics Committee

The Pymble Ethics Committee includes members of the academic and professional staff, external academics and students from Year 8 to Year 11. For discussion is a project from a PhD student who is a teacher at another school. Her study concerns ability grouping in primary mathematics. Everyone has been emailed the application a week in advance and the meeting focuses on whether and how the project will benefit women, girls and the College, and suggestions for the applicant to consider.

There is much to read as the applicant has forwarded her university human research ethics form, with appendices. Students are invited to only read certain sections but most seem to give the whole application a go. The students readily engage in the research question by recalling some of their own memories of learning maths in primary school and techniques they found (and still find) more, or less, effective. There is strong agreement the topic is worthwhile as it can assist students and teachers at our school and others, but uncertainty about the best way teachers should teach. What if the outcomes ask schools to change what they do? This uncertainty helps the group be assured of the value of the project and they are keen to ensure the school learns of the project’s outcomes. Some training for the group is conducted at the same time when notions of risk and harm, confidentiality, gaining active consent and ways to share back after the conclusion of the project are discussed. As the primary students will not be filmed or interviewed, the students focus on what the experience of research will be like for the teachers who participate. They do not want the teachers to feel they must consent, but they like the idea of the teachers being able to attend debriefing meetings with the PhD student to get feedback.

The discussion needs to wrap up as lunch is ending, but there is support for the project. I compile the feedback to share with the applicant, although we’ll soon be allocating specific job roles amongst the committee, so this task will be given to a student in the near future.

Collecting data

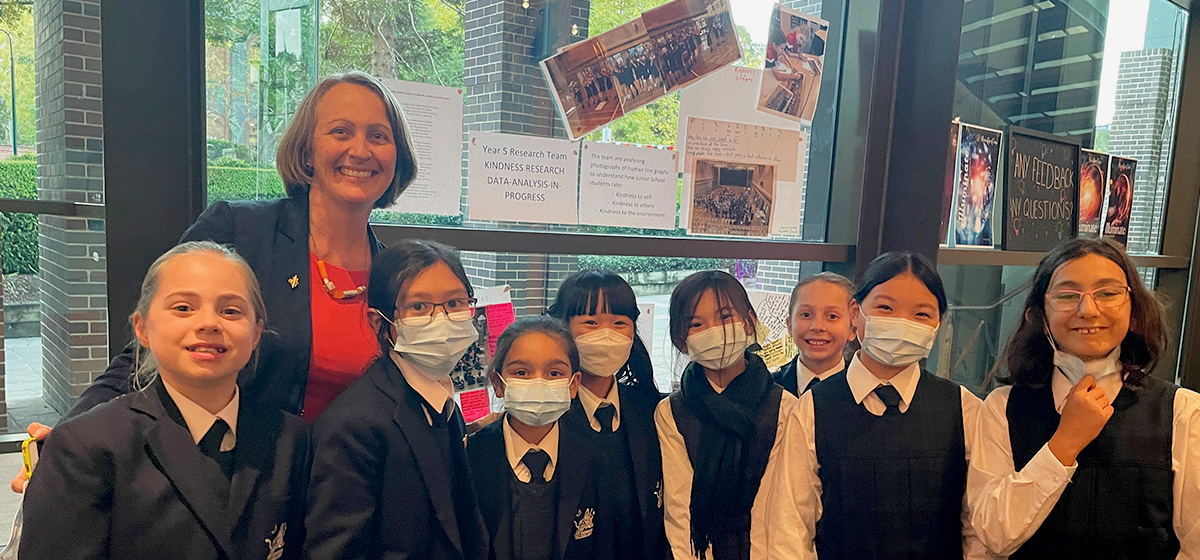

Kindergarten to Year 6 students are working with the Head of Junior School to collect data on kindness.

The Head of Junior School is presenting at a conference and will include the student research in her slides. With limited time available, three 20 minute sessions in the wellbeing program are available to collect data which can be used by the teacher and students.

The data needs to be concrete enough for students to analyse, and conceptual enough to ensure students know their views are represented at the upcoming Kindness Convention the Junior School is holding. The Kindness Captains from each class meet the Head of Junior School and I to brainstorm how kind students think they are and how we can know this. From the discussion, three questions emerge: how kind do you think students at our school are to (i) themselves, (ii) other students, and (iii) the environment. We try forming histograms (human bar graphs) in response to each question but need to make do with small A4 sheets with numbers written on. In further sessions, A3 size numbers are printed for easy use and students stand along a line for each item to rate their views out of ten. A teacher goes to the balcony above the hall to take photos of the histograms. Following this, student leaders from each class work with me to analyse the data. We find that using graphs to understand data is a core part of the Mathematics curriculum, so students bring a lot of knowledge to the task.

Year 5 students analysing data on kindness

Convening a conference

Two senior students are working with me to organise a student research conference, the first we have held. In setting the program, the students create a draft program to balance keynotes, break out and parallel sessions. They want to design a program which invites experienced researchers to share their knowledge with the students attending. I am concerned the program might be too adult-centric and suggest some school student presenters be included, but the student organisers are clear that they and their peers need role models working in different fields of research to teach them what they need to know. There will be time and encouragement for student researchers from different schools to present at the conference next year.

Sessions from the inaugural Pymble Student Research Conference

Capacity building in research skills

These same students also translated an adult-centric idea into student-form. A number of us from Pymble, other schools and universities participate in a monthly journal club to share education research. After I had described the club to the students one day, they asked if they could start one with peers from other schools and run a student version. Junior Journal Club ran for a couple of online sessions but it didn’t work smoothly due to the differences in school timetables. The same senior students have now re-configured the journal club into an academic research club which meets face to face each fortnight with students from our school. The leaders are teaching their peers how academic research articles are written, then they look at examples in different fields of research, and are working towards writing their own. Upwards of twenty students are attending the meetings.

Developing the research culture in our school

Readers with awareness of academic research cultures will recognise that the patterning in Pymble’s research activities for students is building familiarity and capacity, as well as giving opportunities to experience and engage in research. Together, the activities create a platform, as they not only lay out the features of a research culture – where one activity begets another – reading journal articles, writing them, presenting at conferences, attending conferences, building networks, taking and using feedback, designing research projects, participating in research, giving feedback to others, but allow students of different ages and stages to build language, understanding and experience in research. Although strongly rooted in tertiary-level models, our school-based research culture allows students to dip in and out and become increasingly more familiar with what research involves.

As might be expected, research into school-based research cultures is limited, but research into a New Zealand undergraduate program highlights the importance of providing greater opportunities for awareness about and experiences with research for first and second year tertiary students (Spronken-Smith, Mirosa & Darrou, 2014). Positive impacts on student learning include deeper connection with the topic, feeling more motivated and inspired, learning research skills and putting theory into action. Engagement with the research culture at the university at an undergraduate stage also inspires some to plan postgraduate study. This approach is relevant for school students where cultivating a love of learning brings lifelong benefits. Andrew Cheetham, former Pro Vice Chancellor – Research, Western Sydney University, identifies effective research cultures as beginning in secondary school where he asserts research is a learned behaviour. Progressing through secondary into tertiary levels of education, the behaviours associated with research gain more significance and become the research culture ‘that allows us to understand and evaluate the research activity’ (2007, p.5).

Hence, the question which spurred this paper, do tertiary-based research activities provide a good fit and benefit for students at Pymble, seems settled in the affirmative. Critical reflection reveals it has been surprisingly easy to explain both individual research activities to students, as well as to engage them in the full cycle or parts of it. It makes a lot of sense to school students to balance a quest for new knowledge with expectations to apply and test it, share it through some form of output, work with feedback and take cues from the exemplary models (papers, presentations, etc) of more experienced others. It also makes a lot of sense to complete the research activity in a set time frame and with limited resources. School students, it seems, are well placed to appreciate the realities of research! Evidence shows that students at my school are building a research culture and they take from, seek out and alter university research structures to suit. There is an inherent love of and respect for scholarship which motivates students to want to learn how it is done before they seek to do research very differently.

Developing new cultures of research

The second question now comes into focus – could existing structures restrict school students’ perceptions of research? The answer is also affirmative. There is much afoot which will improve research cultures through diversifying them and school students, attending schools with student-focused research centres and/or research cultures, will hopefully produce high school graduates who do not wait until the latter years of tertiary study to contribute to research cultures in their universities, work places and sites of service and volunteering.

There are a number of elements for researchers of the future to consider; namely, ethics, approach and attitude. The following insights from literature conclude this paper and point to meaningful changes that are coming to research cultures in universities, but ones that school-based research centres can adopt immediately, and even begin to lead.

Kindness

The Wellcome Trust is a UK-based, philanthropic organisation which funds science research to improve health outcomes. It recently ‘call[ed] out hyper-competitiveness in research and question[ed] the focus on excellence’ which emphasises research output over how research is conducted (Nature, 2019). Wellcome has been praised for its leadership in working from the funding level to ‘build a better research culture – one that is creative, inclusive and honest’ (Wellcome, 2022); one that includes kindness in its mission.

Diversity

Considering another aspect of research culture, that of multiculturalism and respect for cultural diversity and difference, Barbara Ridley (2011, p. 295) writes of ‘the buzz’ within United Kingdom university research cultures which pivot around people discussing, debating and arguing, quite often with passion and aggression. She highlights a striking difference in research culture in Ethiopia which attends to cultural norms where silence and caution predominate. Building capacity in intercultural research methodologies and mindsets is something that can be explored in school through the diversity of our classrooms and communities. Research will be immeasurably improved when researchers bring a lifetime of experience in celebrating and enjoying diversity to their practice, whatever their age.

Openness

A development in publishing in science journals is questioning openness and transparency through the reportage of data. There is potential for science journals, in their policies, to provide incentives and structures to ensure the reproducibility and transparency of results are communicated more openly, for example, detailing ‘both null results and statistically significant results … [to] help others more accurately assess the evidence base for a phenomenon’ (Science, 2014). The Transparency Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines are eight standards which guide authors and journals in recognising and promoting open science practices.

Also relating to ways research is communicated is the accessibility of journal articles. School students seeking access to journal articles, such as Pymble’s academic research club, are acutely aware of the challenges of sourcing quality research from behind publisher paywalls (the databases available in schools are not as extensive as university library ones) and recognise and appreciate journals which make more articles available via ‘open source’. They see the value in participating in more open source research environments.

Conclusion

The Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (2022) has an extensive collection of articles on issues researchers need be across, including social impact, research integrity, data protection, authorship agreements and metadata; pointing to the construction of ‘the researcher of the future’. Due to the complexity and importance of issues in research, it is reassuring some school students are engaging in research sooner rather than later. Once they get to university, whether the structures and processes guiding research remain the same as today or are vastly different, earlier experiences in research will have shaped the behaviour of the researchers of the future and helped to bring about the diversity of thought research endeavours increasingly require to meet needs in our communities.

People in roles like myself are in positions of immense privilege to enable school students to hold a space in research and with this opportunity comes great responsibility. Teachers and academic research partners working in schools, and adults working with students on research, are already shaping new worlds of research and the experiences, successes, failures, blindspots and illuminations are collectively what build our new research cultures. Today’s school students (tomorrow’s researchers) will be leaders in furthering inclusive, creative and bold approaches to research as they spring further from habits developed in their school years and apply these in their research-rich futures.