Connecting with our feelings: Using collaboration to strengthen social and emotional skill development in Year 3 girls

October 15, 2024 | Junior School

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the social and emotional learning skill development of many students, and addressing the adverse effect of distance learning and the limited social interactions has been recognised as a priority in education (Reimers et al., 2023). Social and emotional skills are vital to student wellbeing, particularly for girls (Kuriloff et al., 2017), and research has demonstrated the significant relationship between student wellbeing and academic outcomes (Fitzpatrick & Page, 2022). This finding has made the teaching of social and emotional skills a priority in education generally and is a specific focus in the Junior School at Pymble Ladies’ College.

The influence of key adult figures at home and at school has been shown (Howard et al., 2017) to shape children’s social and emotional development. It is suggested that the creation of consistent environments both at home and school, where parents, teachers, and students work together to build a shared language and understanding of social and emotional skills will aid in the growth and development of those skills. When looking at the Global Action Research Collaborative (GARC) action research topic of collaboration, I reflected on what this meant when teaching social and emotional skills, and my focus became the issue of how to build this shared language and understanding through collaboration. This led me to my research question: How does active collaboration in Compass Directions lessons strengthen girls’ social and emotional skills?

Action research enables educators to undertake a systematic inquiry into their own practice (Mertler, 2020) to improve and refine their teaching. Utilising an action-research methodology for this project allowed me to create a series of interventions, based on research, where the girls collaborated with each other and their parents to explore different strategies for self-management and self-awareness. Using this methodology allowed me to focus specifically on how social and emotional skills are taught to the girls in Year 3 and provided the opportunity to systematically implement and evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions for developing these skills.

Literature Review

Considerable research emphasises the positive impact of social and emotional skill development on student outcomes, demonstrating that effective social and emotional learning programs enhance academic performance (Dix et al., 2020; Durlak et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2017; Paige, 2021; Wong et al., 2018). Cipriano et al. (2023) extend this body of evidence, showing improvements in behaviour, peer relationships and academic achievement through such interventions. Notably, Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) emphasise that this is particularly important for girls.

The CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning) Framework (2012) takes a systemic approach across several key settings (classrooms, schools, families and communities) to enhance social, emotional and academic learning. Key social and emotional competencies identified by CASEL include self-management and self-awareness. The development of these skills is particularly important for girls, who have been shown to have difficulty expressing and regulating emotions, building resilience, and, therefore, have a greater rate of anxiety symptoms (Australia Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA), 2008). The World Health Organisation (2000) further identifies coping and self-management skills – skills for managing feelings and skills for managing stress – as being essential for the healthy development of children and adolescents. These two areas, self-management and self-awareness, were identified by the Year 3 teachers at my school as areas in which the girls needed further development, so these became the focus for this research project.

Albright and Weisberg (2010) suggest that evidence-based social and emotional learning programs are more effective when they extend into children’s home lives. This notion is confirmed by Dent (2022), who states the importance of parents being involved in their daughters’ social and emotional learning, as well as the need to help girls to understand their own emotions and the emotions of others to successfully navigate relationships. Dent further articulates this importance for girls in particular: “Helping our little girls identify when they are feeling stuck in a mood and helping them work out ways that they can escape the mood, is a really helpful life skill’ (p.84).

Research further demonstrates that collaborative learning, where groups of learners work together to solve a problem, complete a task, or create a product, has major benefits, particularly for girls (Griffiths et al., 2020). These benefits include social benefits, such as the establishment of shared understanding and learning communities; psychological benefits, such as a reduction in anxiety; and academic benefits, such as the promotion of critical thinking skills (Laal & Ghodsi, 2012). Tolmie et al., (2010) take this concept further, indicating that collaborative learning in primary school students not only builds understanding of a given topic, but also provides powerful social effects by improving social skills in students. In the classroom, collaborative lessons, activities and projects provide girls the opportunity to take responsibility for their learning and foster conditions where girls can confidently share understanding and express their ideas without fear of damaging their relationships. It is these relationships that not only help learning but also provide skills development for positive peer interactions (Roffey, 2011).

One strategy that has been used to develop social and emotional learning in the primary school classroom is Circles (also referred to as Circle Time) (Mosley, 2009). This strategy involves the teacher being more of a facilitator once the circle structure and agreed norms are established. Here, the students collaborate within that safe structure, listening to each other, appreciating each other’s perspectives and collaboratively problem-solving together. Visible thinking routines (Richhart & Perkins, 2008), such as “Think, Pair, Share,” are also effective collaborative strategies that can be utilised to explore and deepen thinking and understanding around topics. Teaching girls how to collaborate can also aid the development of important skills such as cooperation, positive interdependence, and peer relationships (Laal, 2013).

In addition to collaboration between students in the classroom, collaborating with families has been shown to be a key factor in determining school success, both academically, socially and emotionally for students and that these partnerships, if effective, also provide significant protective factors to support student mental health:

Schools play a vital role in promoting the intellectual, physical, social, emotional, moral, spiritual and aesthetic development and wellbeing of young Australians, and in ensuring the nation’s ongoing economic prosperity and social cohesion. Schools share this responsibility with students, parents, carers, families. (MCEETYA, 2008, p. 4).

It is the importance of creating a consistent supportive environment, both at school and at home, to support the development of girls’ social and emotional skills that this project sought to explore. The continued development of girls’ social and emotional skills is essential, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic. These skills underpin effective learning, enabling emotional regulation, problem solving, and positive peer relationships (Durlak et al., 2011). By fostering collaboration between students and between students, teachers, and families, a consistent environment and shared responsibility for social and emotional development can be established (Byrne et al., 2020).

Research Context

Pymble Ladies’ College, situated in Sydney, Australia, is an independent school catering to girls from Kindergarten to Year 12 (ages five to 18 years old). The Junior School encompasses over 800 students, including 125 girls in Year 3. This research involved a Year 3 class of 22 students, aged eight and nine years-old, and was undertaken from August to December. I conducted two (sometimes three) hour-long afternoon sessions per week, integrating the project into existing Compass Directions lessons to avoid disrupting the curriculum and ensuring there was no disadvantage to the class. The class was selected due to my prior teaching experience with them in Year 2 and my current role overseeing student wellbeing in the Junior School. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the year group’s wellbeing and social-emotional development also influenced the selection.

Participation in the research project was optional; however, all students in the class participated in the lessons. Parents provided consent for their daughter to be involved in the project, and were sent communications containing information about the project, including how to withdraw their daughter at any time during the project. In addition, the girls were informed of the project, what was involved, and that their participation was voluntary. Parents were separately asked to provide consent for the girls to be photographed and videoed during lessons and interviews and, to ensure anonymity, all names have been omitted from this report.

The Action

The main action of this project was to facilitate the development of self-management and self-awareness skills in the girls. The initial plan was to create a series of lessons where the students collaborated with each other to learn a variety of techniques to regulate their emotions. It was then planned that the students would share these strategies with their families at home on the basis that, to ensure the development of social and emotional skills, there needs to be consistency between the home and school environments (Griffiths et al., 2020).

It was explained to the girls that they would participate in lessons where they learnt and explored different strategies and techniques that they could use to regulate and manage their emotions. The collaborative nature of the lessons was explained to the girls, where they would explore and practice the techniques together, discuss and share their thoughts, and reflect as a class. The project started with some explicit lessons on collaboration, building trust, and understanding active listening, before moving on to self-awareness and self-management skills. Each lesson had a specific focus and included activities, such as reading picture books, role plays, learning a specific skill such as belly breathing, discussions, brainstorming, and reflecting. Each lesson started with the girls seated in a circle on the floor. I also sat within the circle with the students to create a feeling of equality, teamwork, and collaboration (Roffey, 2011).

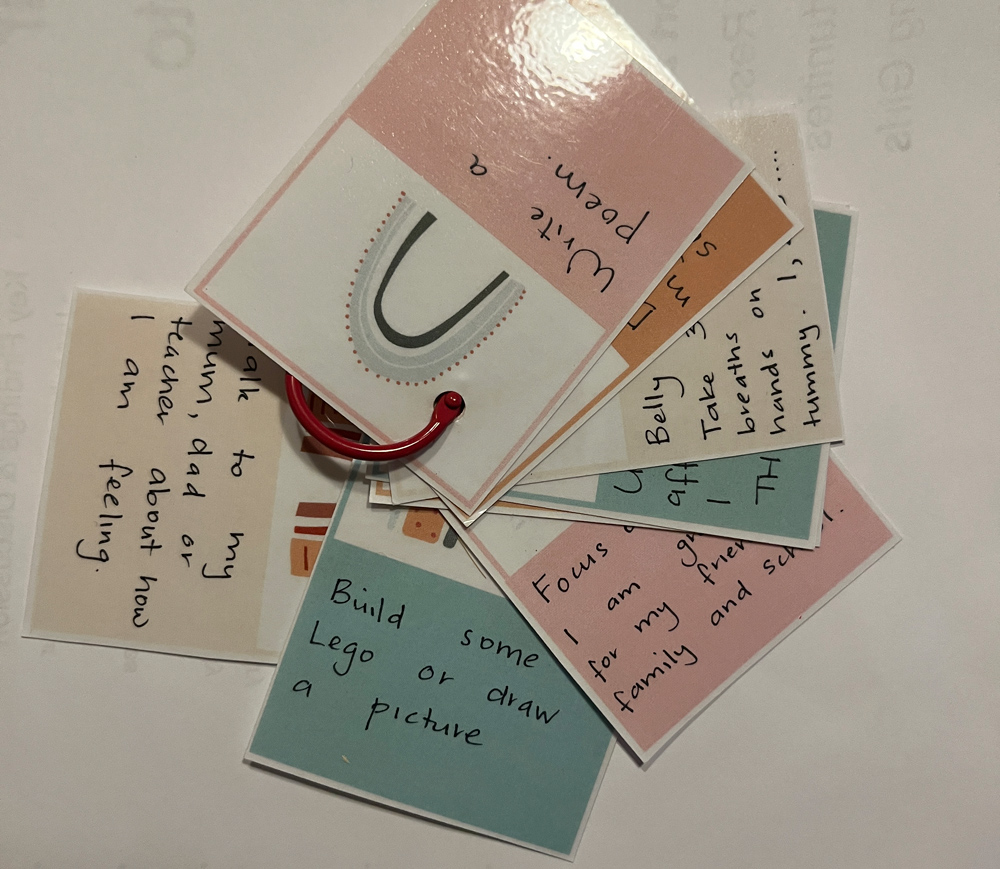

The action evolved over the course of the project following student opinions regarding some of the activities. For example, some of the mindful activities, such as colouring and meditation, evoked strong feelings from the girls, both positive and negative. This made me consider how personal it was when determining what techniques and strategies worked to manage our own emotions and I decided that it did not seem appropriate to simply expect the students to all use the same techniques and strategies. Consequently, I added an extra step to the action whereby the lessons would culminate in the creation of personal toolkit (see Figure 1’) by each student that she could then use when needed.

Figure 1: Lessons culminated in the creation of personal toolkit by each student, such as the one above

Data Collection and Analysis

The project started in August 2023 and, over the course of approximately 12 weeks, the students worked together to explore various social and emotional learning skills to develop their self-regulation and self-management. During this time, I collected both qualitative and quantitative data through a mixed-methods approach. This allowed polyangulation of findings and enhanced their validity, with the aim to create a data set that was credible, accurate and dependable (Mertler, 2020). I used a variety of different data collection techniques, including:

- questionnaires for students, teachers and parents;

- individual student interviews;

- focus groups of parents;

- researcher observations and field notes;

- student work samples;

- student self-reflections (videos).

I first collected data about the social and emotional skill development of the Year 3 girls, as observed by their teachers. This was collected via questionnaire, and I asked questions (using a five-point Likert scale) such as, ‘The Year 3 girls are able to regulate their emotions’ and ‘The Year 3 girls have tools and strategies they call upon to help regulate their emotions when needed’. Following this, I also conducted a baseline questionnaire with the parents, seeking to understand their awareness of the social and emotional skills their daughter is taught at school and their role in their daughter’s social and emotional skill development. This information was used to inform the action that I was going to take in the project and assisted in providing part of the baseline data for the intervention. The same questionnaires were provided at the end of the project to both parents and teachers.

During the lessons, additional data were collected from student discussions, brainstorming using butcher’s paper and post-it notes, and observational notes. Photographs and videos were also taken. It was during these lessons, that I recorded my observations using field notes on the discussions and responses to activities, as well as my observations about the collaboration between the girls. In addition, the girls also completed a questionnaire to share their views of the lessons at the half-way point of the intervention. This was to provide feedback about the different interventions and activities, and served to seek feedback from the quieter students who may have been uncomfortable providing their insights verbally.

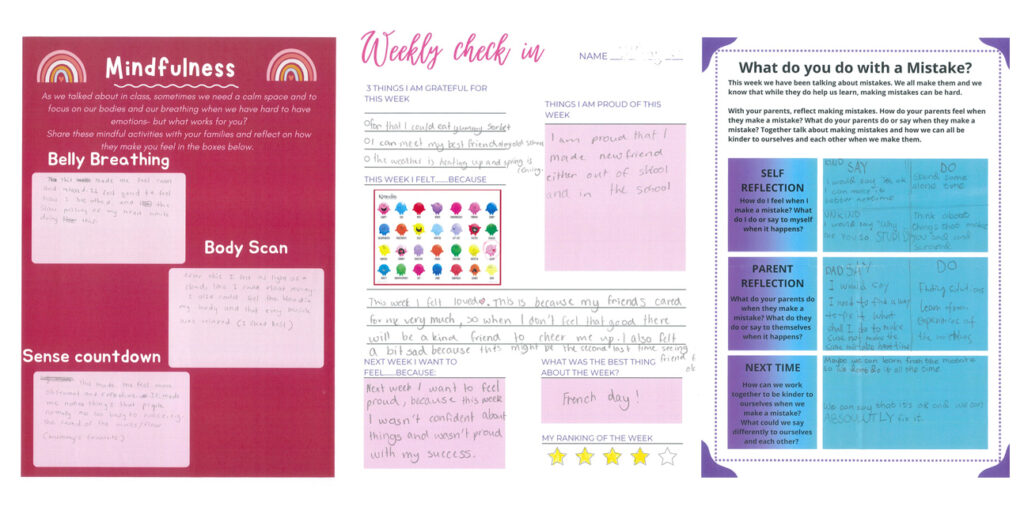

The students completed a self-reflection each week, which not only asked them to reflect upon the specific social and emotional skills learned that week, but also to reflect on their collaboration with their peers and family. This self-reflection allowed me to understand “students’ daily thoughts, perceptions and experiences in the classroom” (Mertler, 2020, p.138). This reflection was also useful in determining how much the students collaborated with their peers and families on these activities and it captured their thoughts and opinions regarding this collaboration. (See Figure 2 for examples of self-reflection done by students).

Figure 2: Examples of self-reflection tools used by students.

Another key part of the data collection process was the focus group interviews with students and with parents. The interviews with the girls were conducted in small groups of three or four, and included some prepared questions for consistency, but also allowed the girls to provide their own thoughts and insights, while providing me with the opportunity to ask any follow-up questions as needed. These semi-structured interviews (Mertler, 2020) focused on the activities in the lessons to develop self-regulation and self-management, plus sought the girls’ views on collaborating with their peers and families on the activities. The interviews with parents were beyond the scope of this research project and will be explored further at another time. Member-checking and peer debriefing (Mertler, 2020) were also used as there was always a second teacher in the classroom during the intervention lessons. Following each lesson, time was taken to discuss the observations made and discuss thoughts about the activities. This was a useful step to ensure the accuracy of the data collected in the lessons.

The collection of a wide range of data before, during and after the intervention lessons in the project helped ensure that the results obtained about any change were clear and trustworthy. Once all data had been collected, I followed the process of inductive analysis to determine patterns and themes to make sense of the data (Mertler, 2020). This was completed by first transcribing any video interviews, merging and sorting the girls’ reflections, my field and observational notes, and the questionnaire results. I developed a coding system to assist processing and collating the data to make connections between the data and the research question and to articulate findings and determine overarching themes.

Discussion of Findings

Initial analysis of the data identified some clear themes, which were used to further analyse and distil my ideas. These themes and patterns were directly linked with my research question and supported my idea that active collaboration between the girls, their teachers and parents to create a personalised tool kit to support emotional regulation would benefit the girls’ development of social and emotional skills. Although there will be further work undertaken on this project, specifically related to the parental involvement, from this analysis, the following themes were identified:

“Joyful Learning” – Collaboration encourages high student engagement

The engagement of the students was essential for the project to be successful, given the personal nature of the lessons. Cooperative and collaborative learning has been shown to be important to aid the development of social and emotional skills by helping foster and build greater student engagement (Dyson et al., 2020). Further, Abla and Fraumeni (2020), reinforce the importance of student engagement with their learning, including social and emotional learning, for their long term physical and mental development. My initial observations of the girls were that, as soon as they saw me in their classroom as they came in (lessons were held after lunch), they were extremely excited and immediately sat in the circular formation on the floor ready to start the lesson. This indicated a high level of engagement.

It was also clear from the interviews, self-reflections and surveys that the girls’ engagement with the lessons and the content was high:

“My favourite time of the week is these lessons as I like talking to the class and sharing my ideas and the activities are really fun” (Student D). The initial lessons set up the plan for the project and explored what collaboration looked like with the girls. Initially there was some trepidation from some of the girls when the concept of collaboration in relation to social and emotional learning was discussed. Some girls later commented that they felt nervous sharing their inner feelings with their classmates, with Student A saying, “At first I was really worried that if I shared how I felt about something people may not be nice to me. Normally I only share my feelings with my family and maybe some best friends, not the whole class.” The initial reservations from this student were alleviated, as her later reflections showed: “This has helped me, like, say my feelings out. Before I wouldn’t really say them out loud and people wouldn’t know what I’d be feeling like, but now they do.”

There were many joys during the project, including hearing the girls talk about their toolkit with pride and an understanding of themselves, witnessing the growing trust in the classroom between the girls and hearing from the teachers that they had seen a change in the girls’ emotional regulation when using their toolkit strategies.

The highlight, however, was hearing from the girls each Monday after they had shared their learning and reflections with their parents. One lesson, in particular, will stand out in my mind forever. This lesson followed the girls sharing and reflecting with their parents about their strengths and talents and setting some goals for themselves together. The girls were bursting with excitement to share their parents’ thoughts about their strengths and talents, some getting tearful sharing with pride what their parents had said about them and their strengths. Seeing the impact of the connections and trust grow between the girls and between the girls and their parents was something I had not really considered.

A safe classroom environment facilitates collaboration

When introducing the project to the girls, the creation of a safe environment in which they could share their personal feelings and thoughts was essential. We initially discussed what good collaborative learning looked like and the girls explained how the establishment of trust and respect is needed to facilitate cooperation and collaboration. As indicated by Griffiths et al., (2020), there are eight constructs identified that lead to collaboration, including trust, mutual respect, shared goals, and shared responsibility. It was clear throughout the project that Year 3 classroom had been created to be a safe space for students to build trust and their mutual respect was reflected in their honest and vulnerable shared reflections. Student A commented, “My favourite thing about sharing with my friends is being able to get feedback and you can then improve and change your ideas. I liked how my friends were honest with me about how I could change things.” While Student D noted, “You get to spend more time with your classmates and can explain and understand more of what they are saying, and it helps to understand how they are really feeling.”

In addition, the girls expressed that they felt they had developed stronger connections with each other in the classroom through collaborating in the lessons. One of the girls reflected that this connection helped prevent some friendship conflict, too: “My favourite part of working together in Compass Directions is we can find out how each other feels and so we can understand each other more instead of having friendship fires” (Student C).

The girls showed maturity and honesty when reflecting with me during their interviews, noting the challenges of collaboration: “Sometimes it is tricky when we disagree as we then have a bigger challenge to overcome” (Student E), and “Working with other people can sometimes be hard as I don’t want anyone to get left out when they need a partner for discussion” (Student C). Student B also remarked, “Sometimes I feel uncomfortable talking in groups and sometimes I don’t really understand what they are talking about.”

A positive comment came from a student who initially found it really challenging to share her thoughts and feelings with the class, her teachers and parents. Initially, she preferred to observe and listen, and only occasionally contributed to the group work when it involved writing things on post-it notes or the whiteboard. In her final interview with me, when she was reflecting on the tool kit she had made and how she felt, she said, “It is hard sharing our feelings with each other to start with but it got easier” (Student G).

Personalised management strategies enhance student agency

Given the personal nature of the content of the lessons, and the need for students to connect with the strategies and activities to incorporate them into their routine to regulate and manage their emotions, it was vital that the girls collaborated when learning the tools and strategies to build their social and emotional skills. Such connection would able them to take ownership and have voice and choice when selecting the inclusions within their toolkit. The enablement of student agency is supported by the literature in the area, where students are empowered through the opportunity for voice in their learning and where learner voice and reflection positively impact learning (Landis et al., 2015).

Agency was demonstrated in the interviews with the girls during the creation of the toolkits and when the girls shared their toolkits with me. Student E commented, “I liked making my toolkit so I could think about the things that worked for me … some were different to my friends, and some were the same as my friends,” and Student A said, “It was funny that my friends really hated mindful colouring and drawing to help them calm down so they did not use it in their toolkit but I have it in mine.” This ownership led to the girls being able to utilise these skills during times of emotional dysregulation, both at home and in the classroom or playground: “Yesterday I used my toolkit when I had a friendship fire with my friend. I got upset and angry and then I remembered the toolkit, so I did some belly breathing and read my positive affirmation. This helped me calm down and then talk it out” (Student D).

Although not part of this report, the development of the girls’ agency was further confirmed through parent and teacher interviews, where the parents and teachers noted the use of the specific strategies by the girls from their toolkits were positively impacting their emotional regulation in the classroom and at home.

Collaboration beyond the classroom enhances family connections

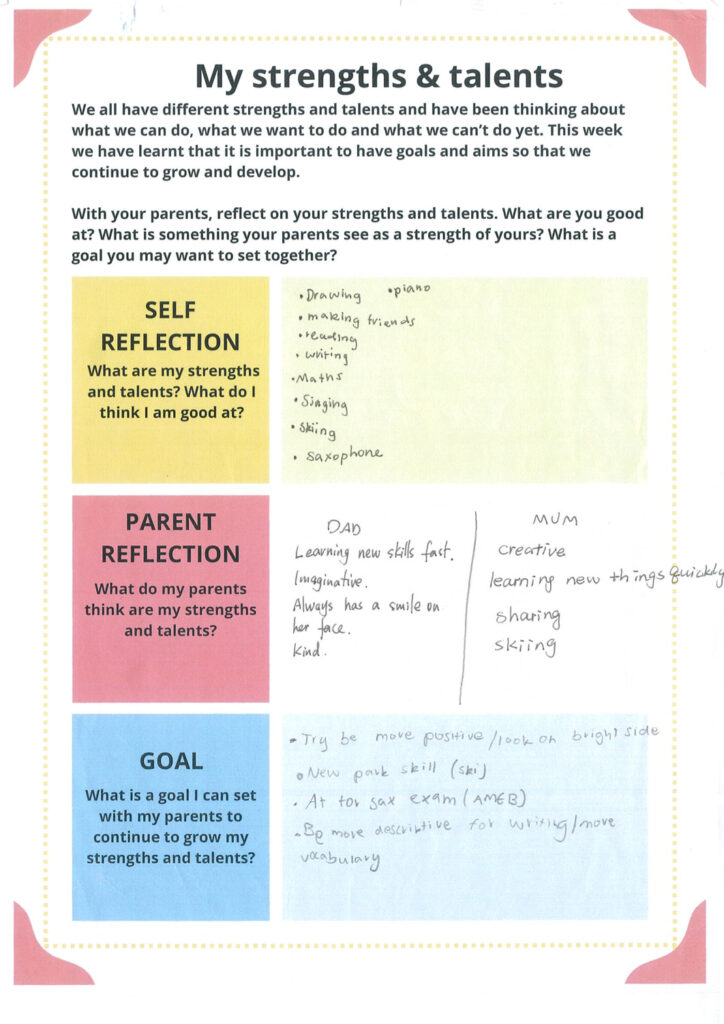

During the interviews and discussions with the girls, a clear theme emerged regarding the collaborative homework with their parents. The girls indicated, almost universally, that having personal homework to do with their parents, that involved discussions and joint input and output, meant greater connection time with their parents. Student F expressed, “I enjoyed that we were able to interact and share together, and my parents helped me to think about the activities and understand myself more.” Student B commented, “I liked listening to my parents and combining our ideas, but I was really surprised by what my mum wrote down about me (my strengths and talents). I didn’t know the things until we did the activity together” (See Figure 3 for an example of self-reflection on strengths).

Figure 3: An example of self-reflection on strengths and talents completed by students.

Although connecting with parents was a very positive result, as the girls loved this time, some of the girls were challenged by this collaboration, as it was not something that they had done before and was difficult for parents to fit into already busy schedules: “It is sometimes hard asking my parents for help and to work on things with me as they are busy” (Student C). This is a potential difficulty of any such collaboration and one that would need to be considered should this format be continued. Another challenge the girls expressed was being open and vulnerable with their parents about their emotions: “Something challenging was I was a bit scared to share my emotions with my parents but using the reflections and the toolkit helped me share with them” (Student G).

At the completion of the project, the girls asked if they could do something similar in Year 4. When I asked why, they expressed that it was lots of fun and helpful working with their friends and their parents about their feelings: “I really liked talking with both my friends and family about my feelings and I love how the homework is actually something that can help you. I really think working on these activities together made me understand my friends better, too” (Student F).

Conclusion

The development of self-management and self-awareness skills in girls is a complex and ongoing process. As research has shown, long-term universal programs and interventions targeting these skills are needed to ensure these skills are embedded. The findings from this action research project confirm that explicit teaching of these skills along with collaboration between the girls and their peers, as well as the girls and their families, creates an environment of shared understanding and trust. The girls were able to create their own personalised tool kit to assist them with emotional regulation by reflecting together and teaching these skills to their families. The teachers and the girls’ parents indicated improved self-management and self-awareness skills in the girls, particularly when managing feelings around making mistakes and friendship conflict, and it was clear that there was some consistent benefit in having strategies and activities across both the home and school environments that the girls could use.

The positive impact of this intervention was clear; however, it also had limitations. One was the difficulty managing the collaboration between the girls and their parents, given this happened at home. Some girls reported that the time needed to share their learning and reflect with their parents was difficult to find each week, which meant that the collaboration between the girls and their parents was not equal for each girl. Another limitation was the difficulty in seeing improvement in the girls’ self-management and self-awareness skills over the short period of the project, particularly as they moved into a new grade at the start of the year. It would be interesting to continue to track the girls over a longer period to see the true significance of this intervention. Finally, a third limitation of the project was the time available to implement the project given the need to fit in with the other timetabled lessons of the teacher so as not to disadvantage the girls in any way.

A future direction for research in this area is to explore how to strengthen the consistency across home and school environments in social and emotional skill development and I will be utilising data collected from parents here as a starting point to build upon. I am also excited to explore how to implement this project or similar initiatives across other grades.