We are in the Fourth Industrial Revolution where extraordinary technological advances are being made, a time where humankind faces fundamental transformation .

(Schwab, 2016)

I remember showing my colleagues at work my first smartphone in 2008: an iPhone. In my hand it felt sleek and slick. Gone were the push buttons of my Nokia – replaced instead with a sensitive, glossy glass touch screen, brightly coloured with cute icons, which when tapped, filled the large screen with an app which led me down a veritable Alice in Wonderland rabbit hole of delight. I remember joining Facebook in 2010 and connecting with family all around the world and loving the posts, likes and messages from friends. I also remember laughing wryly at hours spent scrolling through Facebook posts on a Saturday morning, in bed with coffee.

I was lucky though; I negotiated these advances in technology as an adult, as one who had grown up without a mobile phone and without social media. I had the know-how to reflect and resist.

In December 2022, my son, a software engineer and co-founder of an ed-tech start up, informed our nuclear family that OpenAI had released ChatGPT. As a family with a of love science fiction and keen to explore new technologies, once encouraged by those who know more (my husband is a cyber security operations manager), I jumped onto ChatGPT and had a bit of a play.

One of the first things I asked ChatGPT to do was to write a comparative essay comparing Shakespeare’s tragedy King Richard III to Pacino’s docudrama Looking for Richard. I was jolted by the speed, the clarity, and the points made. And I soon learnt, thanks to my son, that I could develop the answer ChatGPT gave me with more refined prompts. It felt like a civilised conversation with someone who was very willing to help me out. I was a bit annoyed; ChatGPT made conclusions in under a minute, conclusions which had taken me a much longer time to form through research, reading and discussions with my fellow English teachers.

Within the space of an hour I joined the current hype cycle by shooting off an email to the English Department, just before Christmas, attaching two articles: The End of High School English (Herman, 2022); and Will ChatGPT make me irrelevant? (Bruni, 2022). I was in a slight state of panic.

I was somewhat comforted by a YouTube video made by Evan Puschak entitled The Real Danger of ChatGPT (2022) where he posited that “Writing is how we understand the world uniquely,” and in which he reflected that writing was the only way for him to find out who he was and what he believed (Nerdwriter1, 2022). He proposed that it will be up to passionate English teachers to convey the importance to students of writing their own words, while counteracting the allure of an “overconfident chat bot … which is a free magic tool which promises easy grades for less work … in a system which prioritises grades over learning.” Clearly a challenging task, one which I am keen to take on.

Puschak, aka Nerdwriter 1 (2022), also speculated that a year will pass and not much will have changed. Well, I am writing this nearly a year later and while not much has changed in my teaching, much has changed in my thinking, and I am more motivated than ever to engage in deep discussion about the future of education.

At school some students have plagiarised using ChatGPT, and some students, mostly more senior and capable students, have told me that they want to do their own thinking! Relief and applause! But students don’t know what they don’t know and nor do I, but it is up to us, educators, to do what we can, to enlighten our students so that no form of artificial intelligence does a student’s thinking for them (Dede, 2022).

I don’t want to be lost in ignorance, swimming in a fast-moving current, grasping desperately for a helping hand which I find I can’t quite reach, in the slippery, fast paced complex world of the Fourth Industrial revolution. Right now, in my reading and research, I feel as though I am finding a teeny bit of confidence in knowing more about artificial intelligence, like a novice surfer perhaps, thrilled to be finally standing upright momentarily, seeing a possible way forward.

Dear Reader, maybe you are in a similar quandary to me, wanting to discuss what artificial intelligence (AI) means to you. What follows are some initial thoughts and ponderings about what I think students need to know about current artificial intelligence and human intelligence. I know, however, there is a lot more to contemplate, read and discuss with others, well beyond the points made below. Feel free to use the following ponderings to expand your understanding.

1. ChatGPT: It is artificial but it is not intelligent, not yet

At a talk at the Sydney Opera House, we were told by Toby Walsh, Chief Scientist at UNSW.ai, that AI is an alien intelligence and that is it is artificial, an adjective everyone forgets. Though, he also said that artificial general intelligence will be here this century (Walsh & Brooks, 2023).

Professor Chris Dede, educational researcher at Harvard, explained in a podcast that ChatGPT makes calculative predictions, he stated that we would be “appalled” if we knew how little AI currently understands (Anderson & Dede, 2023).

Max Tegmark, Professor of Physics at MIT, who defines intelligence as “an ability to accomplish complex goals,” also stated in his book, Life 3.0, that: “Today’s artificial intelligence tends to be narrow, with each system able to accomplish only very specific goals, while human intelligence is remarkably broad” (Tegmark, 2018).

Dave Snowden, Chief Scientific Officer of the Cynefin company, stated that “we need to stop talking about artificial intelligence and talk about machine learning because that is what we are dealing with” (GRAILE AI, 2023). If we allow students to use ChatGPT “to effectively synthesise others’ written material and regurgitate it,” we shouldn’t be taken aback if AI is better at this than humans because humans are better at abductive thinking than inductive thinking, which is what machines use (GRAILE AI, 2023).

I asked ChatGPT if it was able to use abductive thinking, this was the reply: “I can simulate abductive thinking to some extent by generating plausible explanations or hypotheses based on information and context you provide. However, it is important to note that my responses are generated based on patterns in the text data I was trained on up until September 2021. My responses are not the result of true reasoning or understanding but rather statistical associations in the data” (OpenAI ChatGPT, 2023).

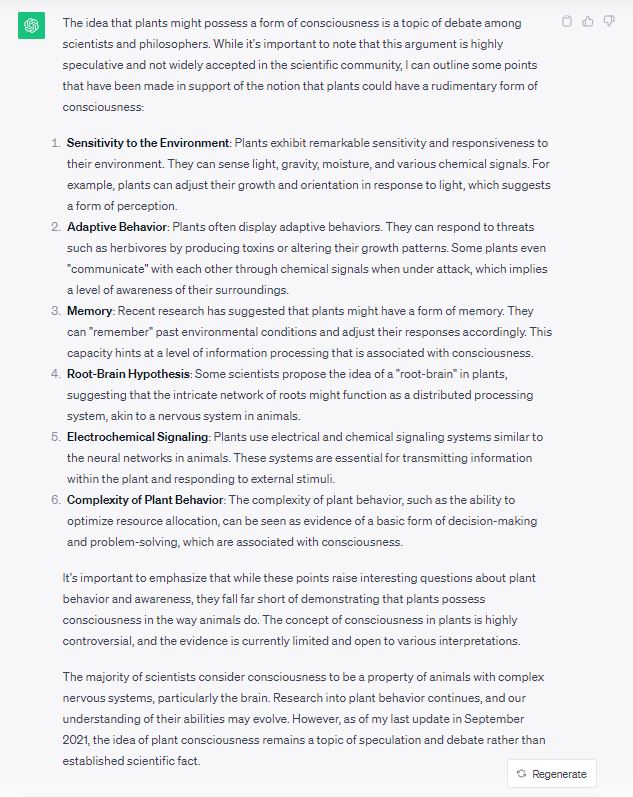

This made me feel rather warm inside until I responded to its suggestion of: “If you have a specific scenario or question where you’d like me to apply abductive thinking, please provide the relevant details, and I’ll do my best to generate a response that demonstrates this form of reasoning” (OpenAI ChatGPT, 2023). So, I did. I asked it to provide an argument for the fact that plants might be conscious. And it did, it was convincing (see Figure 1). It had just revealed to me that it could simulate abductive thinking and the answer it provided about the possible consciousness of plants did not feel like a simulation when I read it. I felt a bit ill at the thought of how easily one can be duped into thinking ChatGPT uses abductive thinking. On a different note, I am not convinced that plants don’t have some element of consciousness.

Figure 1: OpenAI Chat GPT

2. Humans learn with their bodies and have aesthetic sensibility

ChatGPT does not have a body. It is significant to note that “neuroscience now recognises that the brain and the body are so intimately intertwined that they cannot be thought of separately” (Baker, 2022). Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a French phenomenologist of the twentieth century, posited that the mind cannot be separated from a consideration of the body. The body is integral to our consciousness because the body takes an active part in our perception of the world. Merleau-Ponty viewed “dance, mime, painting, music and speech as expressions of thought” (Grayling, 2019). We can consider thinking to be an outcome of our bodily interaction with the physical world. For Merleau-Ponty, “the external world is encountered, interpreted and perceived by the body, through various forms of immersive awareness through action” (Colarossi, 2013). Consider that some human experiences are phenomenologically ineffable, meaning that they cannot be reduced to factual description, in this way an artificial intelligence can never know the experiential nature of seeing the colour red (Colarossi, 2013). Or, for that matter, the feeling of being confronted with a bull elephant in South Africa.

I had the privilege of being in the Sabi Sands Game Reserve in October 2022. On an afternoon safari we pulled up to a group of elephants and our ranger switched off the engine of our open Land Rover. At this point in the late afternoon the temperature was pleasant, and the sky was a haze of thin white cloud. It was quiet and peaceful. We watched the group of elephants contentedly feeding themselves, happy to ignore us, accustomed as they are to safari vehicles. Our heads turned to the left though when our ranger grunted as he perceived movement in the bush. An elephant bull strode up to us with a measured and confident pace and then stood two metres away, sizing us up. Our ranger asked us to be still and silent. Whispering, he pointed out that this bull seemed relaxed but could be temperamental as it was in musth, a period of testosterone surge, which made bulls ready to mate but also aggressive. A five-minute stand-off ensued where time stretched uncomfortably. My mind engaged between wonder and an effort to squash a primal fear of death which held my body still and taut. We didn’t budge. I could not budge; I was sitting high up on the back of vehicle between my husband and someone I had just met. Six tonnes of elephant held us captive as he observed us. I had managed to take photos as he walked up to us, but I didn’t have the courage to disturb him with the sound of the shutter as he stood looking directly at us. I noticed that the woman sitting in front me was bent forward with her hands around her head too scared to look or move. I also noticed the temporin secretion from the ducts on the side of the bull’s face, an indication of musth. The elephant swayed and then placed his trunk on his right tusk. I saw that he glanced down too and then he sized us up again. Then there was a moment where I forgot how terrified I was, when I stared at his face and felt wonder at a sense of his otherness from me, from us. I wanted to understand what it must be like to be him, but I knew that this would be impossible to know. The bull decided to move on, and once he had ambled well away from us, we all made exhilarated exclamations about the experience. The ranger said we wouldn’t have had any time to make a getaway, he said he was reluctant to start the engine anyway, as this might have disturbed the bull and catalysed a reaction.

This may be an extreme example to use for a reference to an embodied learning experience, but I have felt wonder at small creatures too, like the Peron tree frog, who one summer lived in a huge bromeliad outside our front door, fifteen metres from our busy road. We spent almost everyday exchanging stares, which it was happy to do provided I didn’t come too close.

Recalling the experience of the elephant bull reminded me of Immanuel Kant’s concept of the sublime: the overwhelming sense of nature as being greater than human reason (Rohlf, 2023). How would an artificial intelligence be able to realise this concept without experiencing it? The notion of the sublime has associations of wonder and terror but also brings to mind appreciation of beauty. For Kant, beauty encapsulated form, dignity, order, and harmony. True beauty was not associated with utility. We can appreciate this in our consideration of aesthetic experiences and of our reactions to art, or the sense of order and harmony experienced in great pieces of music (DavidsonArtOnline, 2020). Anna Ribeiro, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Texas Tech University, has asked important questions about our aesthetic sensibility: “Could a human being function without the ability to perceive the beauty or ugliness of things? How much would that inability affect one’s capacity to perceive things correctly, to make reasonable judgments about the world, to engage socially and to make decisions?” (Ribeiro, 2014). Essentially, she argues the following: “Homo sapiens is, as Ellen Dissanayake put it, quintessentially also Homo aestheticus; the modern mind is an aesthetic mind. A little observation will reveal that; it is as obvious a fact about us as it is incontrovertible”(Ribeiro, 2014).

David Bohm, renowned physicist and theorist, who was one of the most original thinkers of the second half of the twentieth century, postulated that we need to consider that insight, a fundamental element of intelligence, is a process which combines perception of the mind, our senses, our emotions and our aesthetic appreciation (Bohm, 2004). Max Tegmark (2018) has posited that, because we are not going to be the smartest beings on the planet in the future, we should think of ourselves as Homo sentiens, having the ability to subjectively experience qualia, essentially having consciousness. Consciousness remains an alluring debate for philosophers and scientists.

3. Creativity

Artificial intelligence is not creative, it is generative. One way to consider what it means to be creative is to consider artistic vision and intention. Raphaël Millière, philosopher, is of the view that whilst ChatGPT can generate novel sentences and DALL-E can generate new images, artificial intelligence does not have intrinsic goals. Without a vision or desire we may not consider this type of intelligence, as it exists right now, as artistic (Overthink Podcast, 2023). Creativity is associated with the new, the original. David Bohm (2004) has put forward the argument that this can only be achieved for scientist and artist alike through discovery and play which is not bound by a utilitarian aspect. Instead, Bohm suggests, the key to creativity is the love of learning, crucially with acceptance that mistakes will happen. All teachers love this idea, but in an ironic way, because they continue to be forced to prepare students for the Higher School Certificate.

Why English literature and ambiguity matter so much

This year, I read Shakespeare’s Othello with my Year 11 English class. If you don’t recall, this is the tragedy where the brilliance of the play leaves us staggering and thinking about love, racism, and hatred. Where the outsider, the dark-skinned Othello murders his wife who he believes has betrayed him, and the malevolent Iago has lied and staged the evidence. Othello demands to know why Iago has lied to him and Iago’s answer is, “You know what you know.” My class ruminated over this ambiguous and seemingly enigmatic answer from the frustratingly brilliant and evil Iago. This is the beauty of a critical study, or any study of a literary work; it opens debate and hypotheses about many things. I am most happy to be teaching a subject which requires an acceptance of grappling with complexity and ambiguity, and answering philosophical and ethical questions which require robust discussion, posed to us by great works of literature. Life is uncertain and complex and the question of what it means to be human has never been so important as our current time, it certainly feels that way to me. I recommend Ian McEwan’s (2019) novel Machines Like Me which explores life with a synthetic human and the moral quandaries we might be faced with in the future.

Our Educational Future

As I said above – I still need to read more, write more, discuss, and collaborate with others. It feels to me (and I am sure to many others) that we are in a very new space of thinking about life with non-humans. Rosi Braidotti (2019), philosopher and professor at Utrecht University, challenges the thinking of the Enlightenment whereby human reasoning and achievement are placed at a pinnacle above all other species. Instead, Braidotti champions a posthuman philosophy where thinking is relational and collaborative, where humans and non-humans (plants, animals, and ‘intelligent’ machines) form alliances and assemblages. Her philosophy is one of collaborative morality and ethical accountability and it provides a possible framework for how we can map our future and the future of our students.

The dream of AI is that it can be used to amplify our learning and that together with human intelligence (not forgetting other non-humans), we can reach new understandings. David Chalmers, professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, has written that ChatGPT has shown glimmers of artificial general intelligence and while it does not truly have understanding in the sense that humans do (in terms of perception, action and emotion), he warns that both intellectually and practically, “we need to handle it with care” (Weinberg, 2020).

Whilst social media has connected many teenagers, it has also seemed to be an insidious monster, when not managed well. Our students need to know how AI can be used to spread misinformation and how it can be used against us because it can tap into our human nature and manipulate us (Walsh & Brooks, 2023). Snowden (GRAILE AI, 2023) has serious ethical concerns about ChatGPT as it is trained on data sets which are “biased and epistemically unjust.” One priority seems evident: all our students need to know how machines learn.

Our educational world has brave and wise people in it (like the many quoted above), but unlike Miranda from Shakespeare’s tragicomedy, The Tempest, let us not be naïve, but engage instead in collaborative thought and action.