A new model of resilience

December 15, 2021 | Junior School , Pymble Institute , Research Partnership , Secondary School

Abstract

This article provides a summary of our model of resilience and how it develops. It stems from our work in adults and young people and has been informed by research we have conducted within Pymble over the past decade. It is therefore particularly relevant to children and adolescents as they move through critical developmental phases1. Importantly, our model of resilience regards mild adversity as a necessary ingredient for its development and suggests that experiencing adversity assists in fortifying an individual’s resilience. Generating a comprehensive model of resilience is important, as possessing a robust resource of resilience helps to prevent the development of a range of physical and psychological problems that may come about after experiencing adversity.

What is resilience?

Adversity is stressful and this is associated with poorer mental and physical health outcomes. But despite this, not all individuals who experience stress (even if it is severe and prolonged) develop these problems and, in fact, up to two-thirds of individuals that experience mild adversity remain relatively unscathed2. It is this ability to withstand some degree of stress that is what we term resilience.

Recent models of resilience acknowledge that resilience is dynamic and multi-faceted, rather than being a static trait that is ‘predetermined’ in each individual3. This means that resilience is thought to be determined by a combination of both intrinsic (genes and personality) and extrinsic (environmental) factors, and the interactions between these variables 4, 5.

What is adversity?

When we consider adversity, we think of a challenge or obstacle to be addressed and hopefully overcome. Thus, the concept of adversity is necessarily broad and can include stressors ranging from the psychosocial (interpersonal conflicts such as bullying, parental conflict and divorce), physical (illness and injury), financial (poverty) among others6. Importantly, the severity of adversity can vary significantly, and individuals can experience a multitude of stressors that vary in terms of their impact, from minor stressors to traumatic experiences. Therefore, there is no strict criteria for adversity, and the term includes all manner of challenges and stressors that an individual may experience and may or may not be able to overcome.

When adversity is severe or prolonged, it may lead to an individual becoming increasingly stressed, and unable to cope. This can lead to the development of emotional or behavioural symptoms, which may lead to physical or mental illness7. The model of resilience outlined below details how this may occur, but it is important to note that this model does not state that having a mental illness means a person lacks resilience. In this adversity-driven model of resilience, adversity can assist in building a robust reserve of resilience8, but the emergence of mental illness can occur despite this, due to the experience of significant adversity, or through a person being disadvantaged when constructing their stress-response systems 9.

How does resilience emerge?

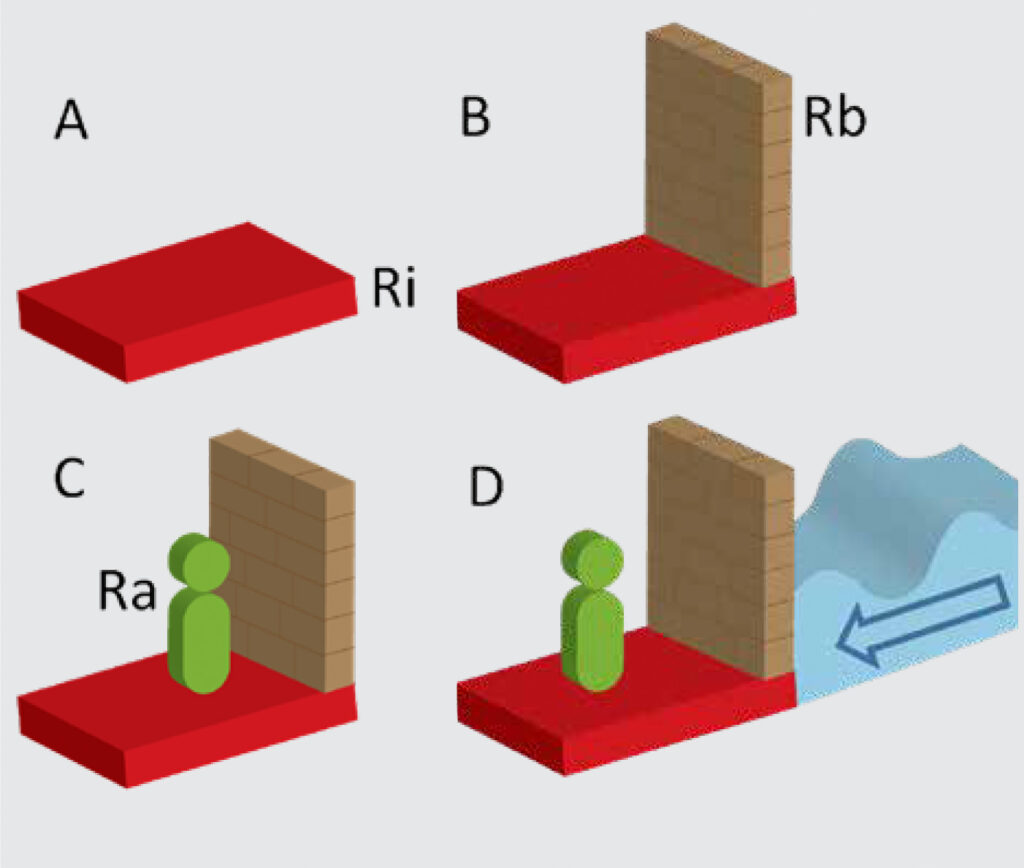

Intrinsic resilience (Ri) can be thought of as the component of resilience that you cannot change per se, as this component is determined largely by genetics and personality factors. This can be thought of as the ‘foundation’ of resilience (see Figure 1). This foundation can be more or less robust, depending on whether there are ‘at-risk’ genes present in the individual, or the individual has personality characteristics which may lead to a less adaptable response to stressors experienced in life.

Figure 1. Components of resilience

In early life, this foundation of resilience (Ri) can interact with the environment that surrounds the individual to develop ‘built’ resilience (Rb). This happens through exposure to a healthy environment and enriching experiences. In other words, generally being surrounded by an environment which is optimal for physical development (e.g., healthy diet, adequate physical activity, sleep) and neurological development (e.g., supportive environment that provides a sense of security, self-worth, realistic mastery and control from an early age) 5, 10. Here, the intrinsic factors that were laid out in the foundation may allow for a strong ‘wall’ of built resilience (Rb) to develop to protect the individual from negative consequences of future adversity. Importantly, this built resilience can occur regardless of how robust the foundation of resilience is in an individual. In other words, even if an individual may be ‘at risk’ of developing illness due to genetic or personality factors, exposing this same individual to an enriching and supportive environment will allow them to develop this ‘built’ resilience to help protect them when they are exposed to stress or adversity later in life.

Following the development of this built resilience, an individual may draw upon resources gathered during this built resilience phase, such as a supportive environment and enriching experiences, to form the foundation of adaptive resilience (Ra). This adaptive resilience draws upon these resources and allows the individual to adapt and respond to future experiences of adversity.

So far, we have discussed the intrinsic factors (Ri) that lead to resilience, as well as some of the environmental factors. However, we have not yet addressed the single most significant extrinsic factor that contributes to the development of resilience – adversity.

Resilience is shown as being comprised of four parts (A to D). The base (red) illustrates intrinsic resilience (Ri), which includes factors established from birth. This intrinsic resilience serves as the foundation upon which further resilience is constructed. The wall of built resilience (Rb) is constructed on the existing foundation and comprising both internal and external factors.

A supportive environment allows for the development of adaptive resilience (Ra), which consists of the resources an individual acquires to be able to adapt and respond to future experiences of adversity. Finally, this system is tested through adversity (illustrated as a wave; D) which places pressure on this system of resilience. It is through this testing via adversity that resilience is achieved.

Considering adversity – what role does it play in building resilience?

Adversity is any type of stressor that can have a negative impact on an individual and the most commonly studied types of adversity are childhood trauma and neglect, and socioeconomic adversity. Adversity can vary in terms of type, timing, intensity, and duration, and these can impact how and when resilience is developed. This can be thought of as an entity that exerts a force, like a wave, on the intrinsic and built resilience that an individual has developed. And because there is so much variability in the adversity that an individual may be exposed to, this results in variability in the ‘pressure’ exerted on the system of resilience that an individual has to hand. This variability in pressure requires corresponding changes in the resilience of an individual to counter the impact of the stress in a proportional way. Thus, in response to this need for strengthening, an individual draws upon their adaptive resilience (Ra) to counter the pressure exerted by stressors.

Does the type of adversity matter?

There are many different types of adversity that one can experience. Essentially, adversity is any kind of significant stressor that an individual may experience, and this can occur at any point in a person’s life. Within scientific literature examining resilience, the most studied kinds of adversity include childhood abuse and neglect, which can impact the development of resilience. Importantly, adversity can vary enormously by type, intensity, and duration and these can impact on the development of resilience, including how and when it emerges.

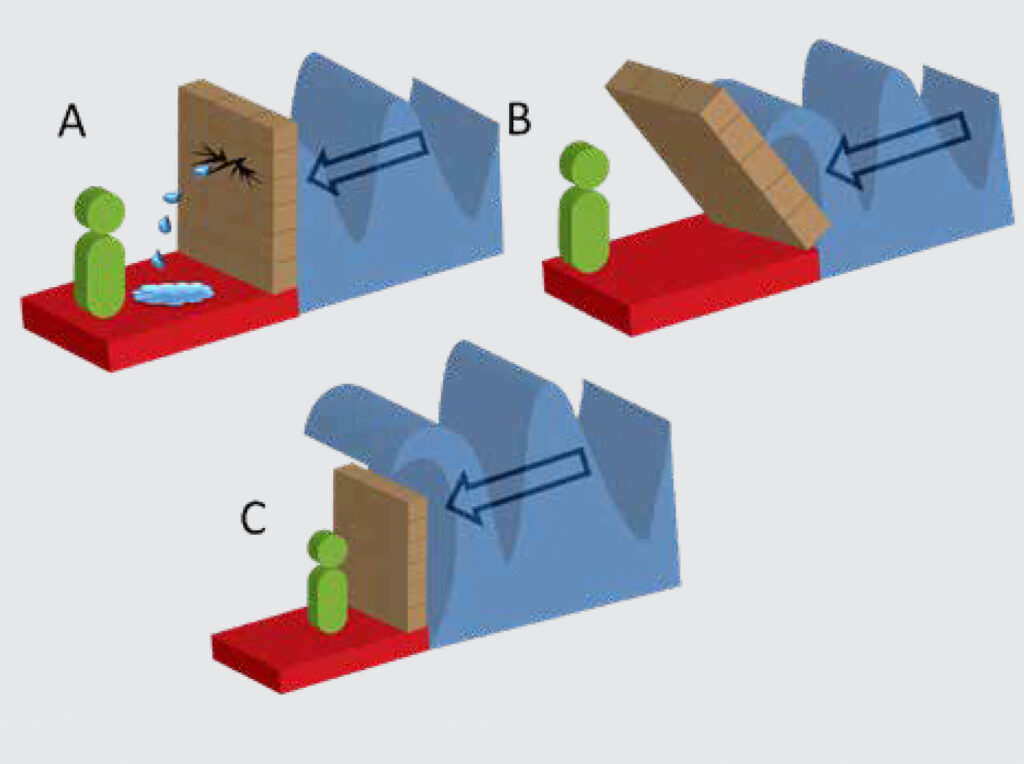

In our model, we have discussed how built resilience can protect us from negative impacts on adversity, like a defensive wall. Here, adversity can be thought of as a wave impacting on the wall (see Figure 2). If the adversity is too intense, lasts too long, or occurs before an individual has had an opportunity to build this protective resilience, then the adversity may be overwhelming and can result in negative consequences. However, if the adversity is not too intense or long-lasting, the force it exerts on the wall of built resilience may instead have positive consequences for the individual.

When the adversity is significant, it may compromise the integrity of the wall. This may result in some damage being done to the wall, by a breach in the wall (depicted as cracks and leakage in A) and by excessive pressure (leaning of wall in B). Alternatively, the adversity may be too severe for the stress-response systems to even begin to contend with the pressure (water rushing over the wall in C). These changes can result in instability systems that determine resilience and an individual’s response to stress. In some cases, they can have negative consequences both psychologically and physiologically for the individual.

Figure 2. How resilience can be impacted by variations in adversity

How does adversity shape resilience?

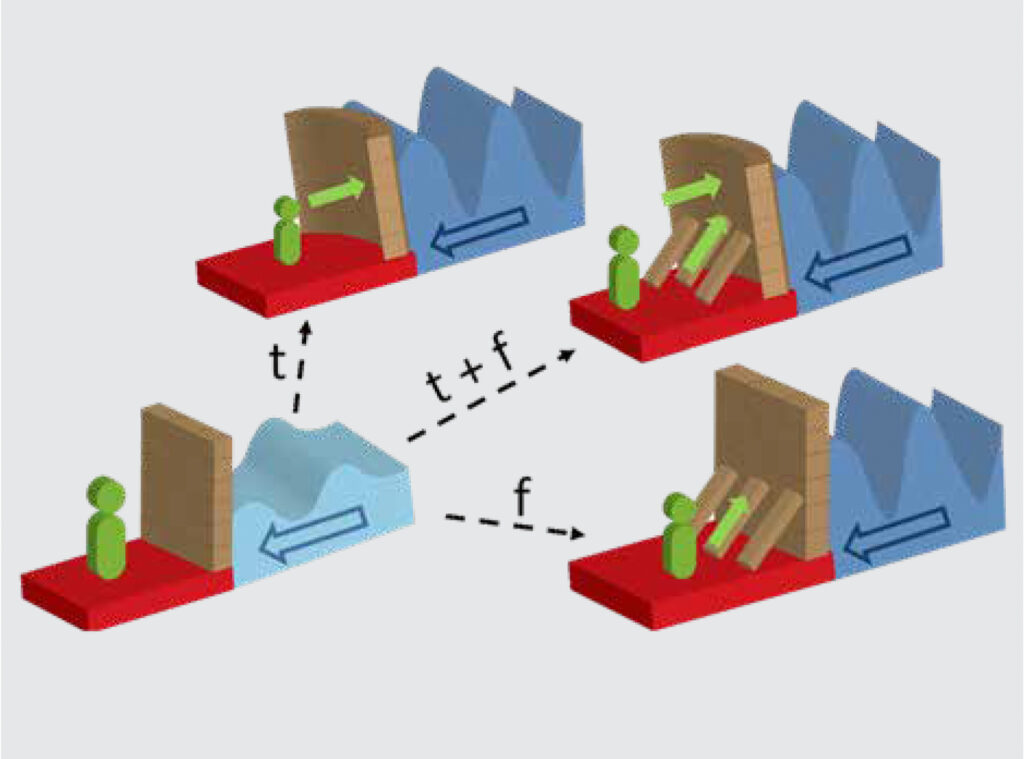

One way through which adversity may positively impact resilience is through a process known as tempering (see Figure 3). In general terms, tempering means “to make stronger and more resilient through hardship” and in our model of resilience, it is thought that experiencing adversity involves the engagement of skills previously acquired to counter adversity that may otherwise have not been engaged, thus making the built resilience component stronger (see Figure 3). In other words, an individual may have built resilience, but this has not necessarily been tested per se. When adversity exerts pressure on this built resilience, in other words it is testing the individual’s resilience, it allows them to engage in skills that they may have acquired but not practiced, and thus their resilience is strengthened. This is analogous to restructuring the wall of built resilience to make it more structurally sound, and although nothing is necessarily added to the wall, it is now better suited to handle the pressure of adversity.

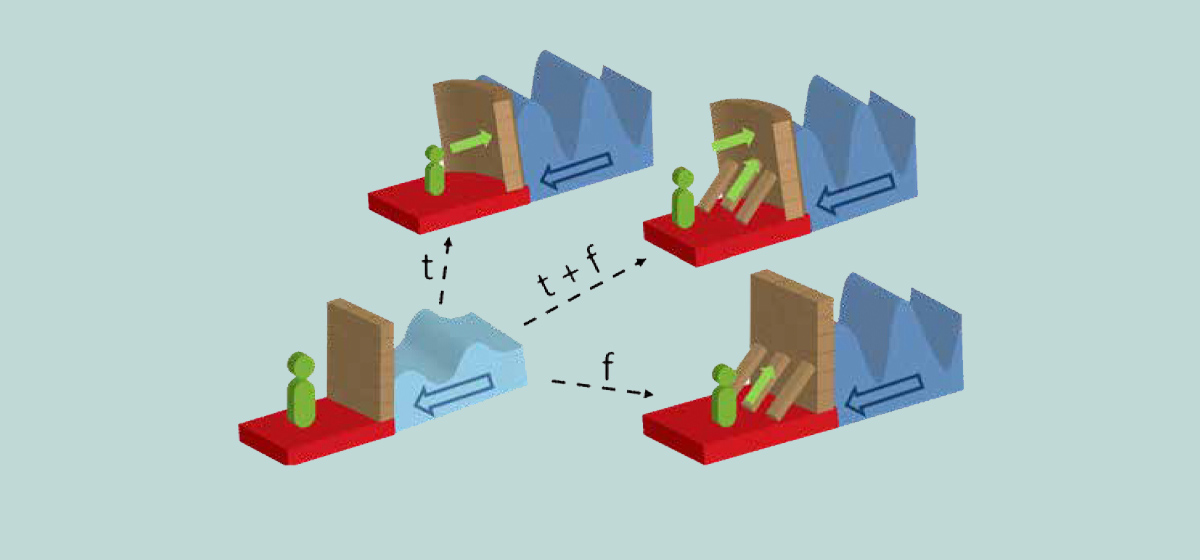

Figure 3. Tempering and fortification

However, while tempering is useful and it may produce some immediate strengthening, it does not introduce new skillsets and may in fact make the individual’s built resilience less flexible or brittle. This is why fortification is also needed to ensure stability and strength.

In our model of resilience, fortification involves the acquisition of new skills that are learned to reinforce the built and tempered wall of resilience to withstand the stress of adversity. However, fortification takes time as the individual is acquiring new skills to cope with the pressures of adversity. Thus, if intense or prolonged adversity occurs before this process of fortification has occurred, and the person cannot draw upon previously acquired skills to temper the built resilience, the adversity may be overwhelming. It is important to note that for both tempering and fortification to occur, adversity must be present. Therefore, in order to develop a robust resource of resilience, the individual must experience some adversity in order to trigger these processes.

As an example, an individual may have experienced some adversity as a child, such as the divorce of their parents. This experience was stressful for the individual and shaped their psychosocial development. The individual developed skills to cope with this adversity, and their stress-response systems may have adapted to this experience. Later, as an adolescent, the individual experiences a new stressor, such as bullying by peers, that requires the same skills utilised in their previous experience to cope and overcome this new adversity. This is what we would describe as tempering, wherein the individual’s existing skills, which may have been dormant until this time, are re-engaged due to a stressor placing pressure on their stress-response system. This experience ultimately strengthens the individual’s resilience, and they are able to cope and overcome this challenge.

But there are a variety of challenges that an individual may experience that are very different by nature and require a new skillset to navigate and overcome. So, for example, the individual may also experience a new type of stressor that they have not experienced before, such as a loved one experiencing a serious illness. Here, the individual needs to learn new skills and the stress-response system gains new strategies for dealing with this pressure. This is what we would describe as fortification, where an individual acquires additional skills that are added to their existing resources used to cope with adversity. The combination of tempering and fortification is believed to aid in developing robust resilience and a stress-response system that can cope with a variety of future stressors.

This schematic diagram illustrates how tempering and fortification strategies enhance resilience in response to adversity. The ability to withstand increasing pressure (represented by the dark blue arrow) requires active engagement (represented by green arrow) to either employ pre-existing skills (tempering (t) for use in new contexts (depicted by curvature in the tempered wall) to produce tempered resilience or acquire additional skills (fortification [f]; depicted by braced wall) to ‘further build’ resilience culminating in fortified resilience. To enhance stability, the tempered wall also needs fortification (depicted by the tempered and fortified wall (t + f). Tempering and fortification ultimately repair, modify and strengthen the integrity of stress-responsive systems, to produce adaptive resilience (Ra). The intensity of adversity is depicted by the colour change from a lighter (low intensity) to a darker (high intensity) blue colour. The duration is depicted by the wavelength, which can be intermittent, short, or prolonged.

Implications – what does this all mean?

Our model of resilience conceptualises adversity as the catalyst that drives the processes leading to its development. Experiencing adversity places ‘pressure’ on an individual’s stress-response systems, and without such ‘testing’, resilience cannot be fully developed. Therefore, resilience is adversity-driven and is likely forged in adolescence – a time when neurobiological changes are most active.

This model also suggests that situations or occasions in which the adversity experienced is excessive, can lead to impairment in the same stress-response systems which can result in negative impacts upon physical or mental health, potentially resulting in the development of problems. It is important to note, however, that this model does not suggest that mental illness and resilience are mutually exclusive, and in fact an individual with mental illness can still possess resilience.

Conclusions

Developing and fostering resilience is critical to ensuring health and prevents the development of physical and mental illnesses. In addition, in individuals that do experience these illnesses, resilience can assist in achieving recovery and preventing recurrence of illnesses. Therefore, if we can understand the underlying processes through which resilience is established and fostered, we can begin to develop interventions to promote this process and ensure its completion.